Welcome back! Recall that in part 1, I established that I was treating the “queer male community” not simply as something out there waiting to be understood, but rather as something I actively shape through my actions around it. In part 2, I raised “seeing” others or ourselves as an action, and suggested that the very idea of a queer male community “out there” may lead to exclusion rather than connection.

But what is queer male community?

To better understand this elusive community, we could stipulate a definition based on what unites them. For example, “queer male community is the men who sashay down the street every June,” or, “queer male community is the men who stan Nicki Minaj,” or, “queer male community is the men who feel guilty about shopping at Hobby Lobby.” But if we choose only one definition, everyone who doesn’t fit has to sashay away.

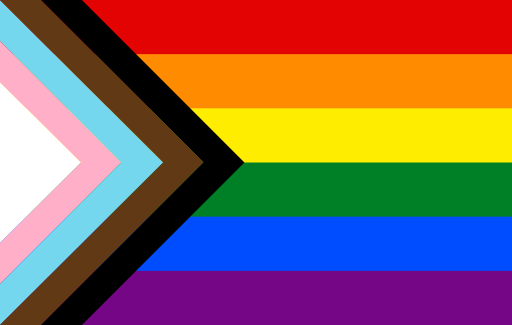

Perhaps at Stanford, the expectation of a cohesive queer community is more pronounced. Stanford, close to the global center of the Pride movement in San Francisco, draws students from around the world, even from as far as San Diego. But few seem to be happy with the way things are. One perspective on this community names some rather blunt categories: the “gay frat mafia,” “activist-y queers” and many lonely people in the middle. Another perspective on the same community: “gays who think getting attention is normal, co-ops and people either aloof or scrambling to save their sanity.” Either way, getting caught up in “perspectives” may only distract from what is actually happening.

Instead, ethnography allows us to leave categories behind and see what emerges from action — the doing of the queer male community, to sound racy. (It’s not a race, but there has been a lot of action over here.) Everyone’s actions matter, but I have graciously volunteered to show you my own, from coming to Stanford three years ago to starting my Grindr profile three months ago. Here it goes!

Opening me

When I first reach Stanford, I enjoy many new friendships. But where are the queer men? Do tell — I’m craning my neck, but seeing only compost bins. A few queer men drift by, but the Winds of Freedom tend to blow them away.

I eventually join Tinder: The name is apt, because I collect many matches across the land, each of which improves my life for about four seconds. But seldom is there a spark of motivation for anyone to send a single message, and most possibilities for connection go up in flames. Then Hinge a.k.a. Cringe: the app with “prompts” users can answer on their profile to lubricate their initial conversation. Common answers to these prompts, however, tend to make profiles blend together until they become indistinguishable. Still, I start a committed relationship with the quest to understand the Hinge algorithm, which ends poorly.

So, I run out of reasons for avoiding Grindr. In terms of user interface, Grindr is the app equivalent of biting into an apple core while stepping on a Lego brick. Even so, the app can get the job done — if the job is booty calls while I’m getting ready for bed, plus an invitation onto an older man’s boat. But I know exactly what I’m getting into, and I’m ready to use Grindr for my own purposes.

So, onto my next action: making a Grindr profile. There is a plethora of fields, so this will be ethnographic “fieldwork” if there ever were such a thing!

The basics. To fit in, for my name I add only my first initial. I also add a few pictures of myself, a below-average-height man of South Asian descent whose body hasn’t changed in several years. Grindr doesn’t check or update anyone’s age, so I guess I’m Forever 21. I also list my gender identity — cis male, though that doesn’t stop me from taking a plucker to my unibrow. Finally, I list my relationship status, which I will later learn doesn’t matter to a single person on the app.

“Height” / “Weight.” As it turns out, signing up for the “queer male community” is not so different from my intake at a primary care clinic. I list my height, because maybe it’s part of my overall “vibe”? Height would at least be useful to know in case someone needs to stand on a stool at the wedding, but I doubt anyone on Grindr has already made a down payment for the wedding venue (apart from the users who are already married). Weight, on the other hand, should never be relevant information, unless the older man’s boat has a strict capacity.

So, I leave that field blank.

“Tribe.” In Grindr speak, these are twelve categories of people grouped by vague characteristics. The categories are absolutely wack — without context, reading them evokes a picture of animals and their keepers. And apparently, “trans” and “poz” capture the same nuance of human experience as “bear” and “leather.” Still, the tribe concept has a strong hold, supposedly to help users identify others of their preferred type. In addition to tribe, there is yet another field for “body type” — as if the torso pics leave any details to the imagination!

Either way, I don’t quite belong to a tribe. I’m not sinewy enough to be a “jock,” nor jaded enough in life to be “rugged.” I’ve been referred to as a “twink,” but I don’t have the attributes of a canonical twink, as my body is surprisingly shapely.

To put my tribe another way: If ever faced with a lion or some other predator, I wouldn’t be nimble enough to scurry away like Troye Sivan, nor strong enough to put up a fight like Ricky Martin, nor savvy enough to sit the lion down for an interview like Anderson Cooper. “The middle is lonely,” one might say. To make matters worse, I have chronic acid reflux — but most potential partners in a gay encounter, and most hungry predators in the animal kingdom, will forgive such details.

So, I leave that field blank.

“Ethnicity.” I’m of South Asian descent, which makes it hard to turn myself into conceptual art. It’s possible, but it takes far more ingenuity. For example, take the 2017 critically acclaimed film “White Boy Bonanza” — er, I mean, “Call Me by Your Name.” When Timothée Chalamet bequeaths his seed to a peach, the Academy lauds his bravery and calls it a cultural moment. If I do it, my friends yell at me for being irresponsible and wasting food. (Or at least I hope they would; I’ve never actually tried it.)

So, I leave that field blank.

“Role.” In gay lingo, some examples of roles are “top,” “vers” or “north-northwest.” (For readers unfamiliar with these terms, they are methods for baking cupcakes.) Apparently, “bottoming” requires the most preparation — like doing the readings before class? I’m happy to list “vers” for now, since I’m a Zumba instructor and think I could play any of the roles ironically.

Stepping back: limits without limits

Did that feel like a lot? I had a splendid time making my profile. Yet navigating a multidirectional totem pole of categories wasn’t always so peachy. Even so, with my methodology, none of these categories — “South Asian,” “twink,” “north-northwest,” even “man” — is objective and mind-independent, coming from everywhere and nowhere. Like the queer male community itself, they have emerged from the actions of everyone before and around me, including the very acts of seeing and being seen, naming and being named.

Even when we agree on the category, maybe we don’t agree on its stipulated definition. Take tribes, for example: How many peaches do I have to transgress to be an eligible twink? How sinewy and uncomfortable in airplane seats to be a jock? Am I tall enough in inches to be either? While I’d be curious to conduct ethnographies of these two Tribes, I’m not sure even they would have the answers. (Either way, they seem too engrossed in their iced coffees and protein powder, respectively, to talk to me.)

Some tribes, including twink and jock, emerged from decades of action around mostly white examples, now reinforced through Grindr. Personally, they were imprinted on me long before I had the vocabulary to name them. As the Grand High Supreme Court herself would say, “I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it.” But she didn’t mention that we had to collectively decide it was worthy of being named in the first place.

If connecting with queer men comes with uncertainty, perhaps categories give us a cultural script to hold. But when mixed with personal anxieties, companionship may teeter toward comparison, between one another and these projected categories for our existence. Those most visible in their category may even struggle to leave, or risk being objectified. On the other hand — like me, before I ran out of reasons for avoiding Grindr — we may struggle to fall into place or risk slipping into incoherence. The question isn’t how many boat invitations we receive, but how visible we are in the community we thought was worth defining. The problem is worse when Grindr, the gay app equivalent of pee jars, is one of our only touchpoints with that community.

Grindr offers a free filter feature to narrow down users who make it onto their grid. Currently, users can filter by tribe, age and reasons for being on the app, like “relationship” or “right now.” Before the protests for racial justice in 2020, the third decade of the third millennium of the Common Era, you could filter out users from your Grindr feed explicitly on the basis of their ethnicity.

Grindr also offers paid subscriptions within the app. Today, you can still use “Advanced Filters” — height, weight, body type and others — with Grindr XTRA for the price of $19.99 per month. (The day this article went up, Advanced Filters were offered for free in my area to promote paid subscriptions. Personally, I’d prefer a modest dinner in Palo Alto!) An even more “exclusive” plan, Grindr Unlimited, comes with the bonus of impaired executive functioning: “Nothing will delay your satisfaction.”

In case you’re wondering what Grindr has done about its many issues, you can check out their feedback forum, which has been an important platform for users to educate and hold one another accountable. Just kidding! (Seriously, read through the comments at your own risk.)

But Grindr is only one touchpoint of the queer male community. Even without it, I can stipulate a more inclusive definition: people who may or may not know who they are, but as soon as they name it, someone wants to filter them out.

If seeing is an action, so is hiding. In what I don’t list on my profile, am I rebelling against the cultural script or succumbing to its power to exclude? For everyone else still in hiding, what will it take for them to become worth seeing? Remember that we got here by everyone’s doing, so the answers will depend on more than gymnastics from anyone’s “perspective.” As for my actions, I guess you could say the cat’s out of the bag! But if I get any ideas with peaches, I’ll be sure to lock the door behind me.