When the University reaffirmed plans to bring juniors and seniors back to campus in the spring, students were met with familiar messaging: Stanford was prepared to invite students back to campus after shutting down last March, public health conditions permitting. They had canceled similar plans twice before, in both the fall and the winter.

Each time, while disappointed students bunkered down for another quarter of distance learning, the University made provisions for students with special circumstances to live on campus. For example, students in strange time zones or without a place to go could come live at Stanford and log on to Zoom classes from a campus dorm room.

But unclear messaging and an evolving application process each quarter has left some students frustrated and stuck. Denied housing, they face learning challenges, safety complications and mental health struggles, among other obstacles.

The Daily spoke with frosh and sophomores who applied for special circumstance housing for spring quarter and were turned away. These students have been granted pseudonyms to maintain their privacy.

Students seeking consideration for special circumstances housing for the fall and winter quarters were able to submit an application through a Stanford Qualtrics survey emailed to students in Re-Approaching Stanford newsletters. Students would not need to reapply for housing once they had been approved through the review process.

However, the process became less streamlined for the spring. Unlike fall and winter, students say the spring application was barely advertised. Students who seek housing could submit a help ticket through Qualtrics to be assigned to an residence dean (RD) reviewer, or could reach out directly to an RD.

Izaak, a frosh, who was approved to live on campus for the winter quarter, ultimately decided not to move to campus in light of the surge of COVID-19 cases at the time. But when their parents struggled with employment and their grades declined, they emailed the University’s Undergraduate Student Support, an email address for general student inquiries, requesting on-campus housing for spring. Already the process was different.

“In the winter there were multiple emails telling people to apply for special circumstance housing if needed. And the process itself was just submitting a form rather than a whole interview process,” they said.

For spring quarter, RDs have been meeting with students to learn more about their situation, and each case is reviewed by a panel of student affairs professionals “to determine an appropriate course of action, referral to additional resources, or follow up from a member of the undergraduate student support team,” according to Student Affairs spokesperson Pat Harris. Applications are reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

Several students described the meetings as brief and felt the RD knew the outcome of their case prior to meeting with them. In Izzak’s case, they spoke with RD John Giammalva, who told them they didn’t qualify but that had they applied last quarter, they would have been accepted. Giammalva declined to comment.

“I can understand their difficulty in accommodating special circumstance people with all the juniors and seniors moving in,” Izzak said. “However, the notion that some people can be granted special circumstance housing in the winter and not in the spring is just inconsistent and harms the people who may need it.”

Before they can move on to the panel phase, students must come prepared with an alternative to on-campus housing — a requirement students found confusing.

“As part of this process, we encourage all students to explore all options and resources available and to make multiple plans so they are well-prepared for the variety of outcomes and circumstances any student may encounter,” Harris explained. “This includes working with campus partners such as the Financial Aid Office and Opportunity Fund to connect students with the resources they may need for off-campus housing.”

Michelle ’23 lives with her mother and sister in a small apartment. Her mother is a healthcare worker and her sister, with whom she shares a bedroom, works early shifts, which prevents Michelle from completing assignments in the space at night. Michelle would alternate between taking classes in her room and living room — which is less than five feet away from the kitchen — during the fall and winter quarters. She faces mental health struggles at home and a heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 because of her mother’s job. She said her environment does not support her learning. She applied for special circumstances housing for the spring quarter and was rejected, despite citing problems participating in remote learning in her application.

Michelle reached out to multiple RDs in an attempt to appeal the rejection. One RD responded to her email, and later she had a brief Zoom call with a different RD, where her request was again rejected. In both instances, the resident dean she spoke with pointed her to Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS).

“That’s not the problem,” Michelle said. “My problem is that I don’t have enough space to study and I lost motivation because I don’t have enough space to study. That affects my mental health issues.”

She explained that RDs told her she had to be in an “emergency situation” in order to be allowed back on campus for spring.

Alex ’23 had a similar experience while attempting to get approval for on-campus housing. He had a brief call with the same RD Michelle spoke with on Zoom. This dean suggested reaching out to the Office of Accessible Education (OAE) for accommodations that would possibly make him eligible. The complex process deterred Alex. He is grappling with isolation, mental health struggles and remaining a closeted queer student at home.

Both students expressed frustration over the lack of transparency and clarity in the housing application process, and more specifically, what qualifies as “special circumstances.” They both said they were disappointed with their short interactions with the RDs.

“Our RDs cannot disclose details about individual student requests and/or circumstances,” Harris wrote in response when the Daily reached out to RDs for comment.

According to Harris, there is no formal appeal process and “students with new or additional information about their circumstances may, for instance, share this information via ServiceNow ticket or outreach to Residence Deans for further consideration. In some instances, the Dean of Students and other Associate Vice Provosts for Student Affairs may review new information from the student.”

About 5,100 graduate and 1,500 undergraduate students with approved special circumstances live on campus, according to a Feb. 25 email from Marc Tessier-Lavigne and Persis Drell. But the definition for special circumstances has fluctuated a bit between each quarter.

According to Harris, the University received a total of 2,438 requests for special circumstances housing, and over 95% were submitted for fall and winter quarters. Almost three-quarters of requests for fall, winter and spring were approved, according to Harris, but she did not comment on the percentage of denied requests for spring quarter only.

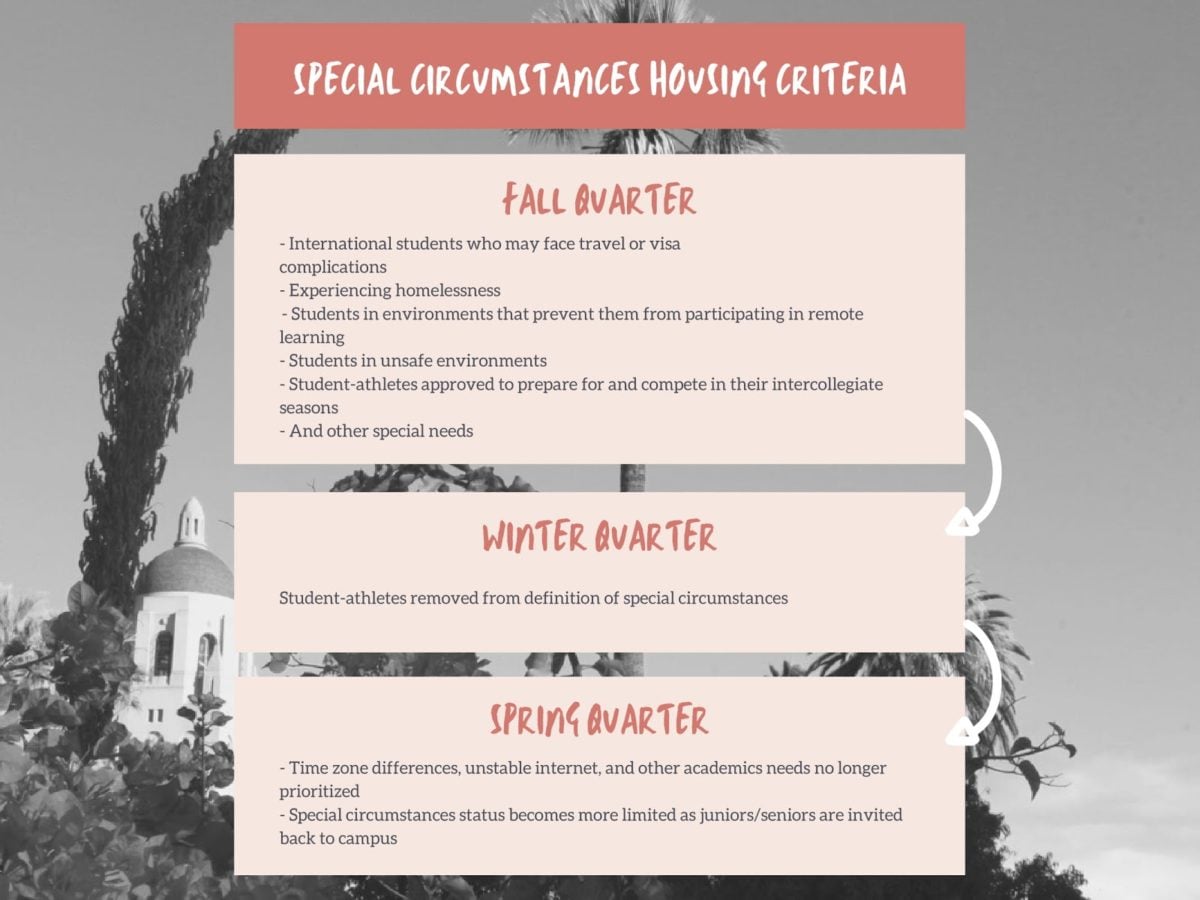

In the fall, special circumstances included: students facing housing instability or living in unsafe environments, international students who struggled with travel or visa complications, students in environments that hinder their ability to participate in remote learning, student-athletes on campus to train or compete or other special needs. The University did not include training student-athletes in winter quarter special circumstances housing eligibility.

What are the criteria for special circumstances housing in the spring? It depends on who you ask. Harris directed the Daily to the definition from the fall quarter, which included athletes. Applicants report usage of different criteria by different RDs, however.

Vilma submitted a COVID help ticket requesting to live on campus during the spring quarter due to an unsuitable learning environment. From her house in a rural town, she logged onto Zoom at 5:30 a.m. to attend a class with mandatory attendance. The town experiences power outages once a week and her house has limited Wi-Fi access. This made it difficult to keep up with classes and her grades suffered. After two weeks without a response to the help ticket, she reached out to RD Klareese Donnelly, who told her during a Zoom call that academic circumstances such as time zone shifts or an unreliable internet connection no longer made her eligible for special circumstance housing.

“She advised me to take a flex term (not possible because of a summer internship) or a leave of absence if I couldn’t manage my spring classes from home,” Vilma wrote in an email. “My main concern with that was not getting out of my home environment and not having anything to do at home besides working my minimum wage job.”

Later, she emailed Undergraduate Student Support and Donnelly a two-page letter she wrote with her mother elaborating on her situation and why she did not apply for fall or winter housing. Donnelly responded a week later stating she reconsidered her initial decision in light of the additional information and forwarded the frosh to the housing application. She was ultimately accepted.

“It’s crazy because so many people are being turned away this quarter who easily would’ve been accepted if they had applied in a previous quarter,” Vilma said.

As juniors and seniors move in to campus, students turned away from special circumstances housing are left to find alternatives or endure their situations. Some like Michelle have decided to rent housing with peers, though she initially believed finding on-campus housing would have been an easier solution to her situation. Others remain at home.

“I would have liked more transparency,” Alex said.