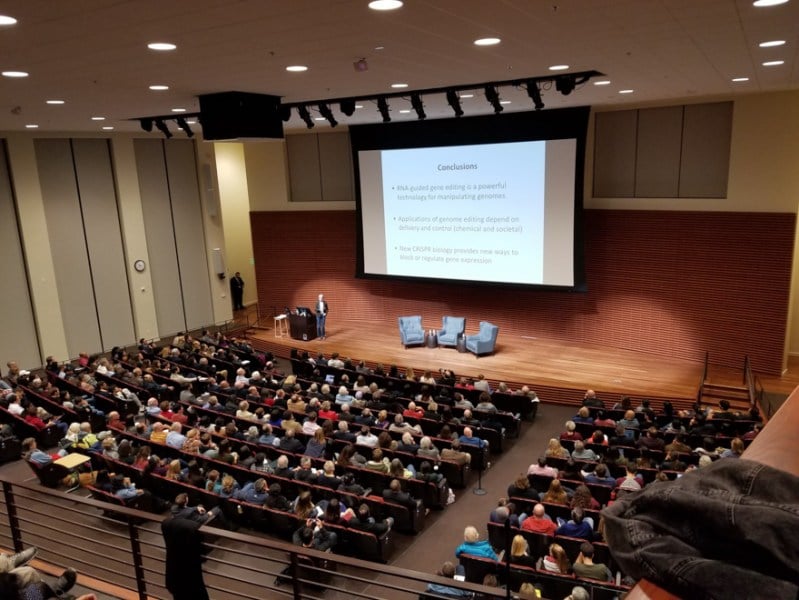

CRISPR gene-editing technology co-inventor Jennifer Doudna addressed the opportunities and challenges of editing genomes in a Thursday conversation with political science and ethics professor Rob Reich and genetics professor Kelly Ormond.

“The major bottleneck for moving forward in the clinic is delivery,” Doudna said. “In other words, how do we safely introduce the machinery necessary for genetic engineering?”

Since former Stanford postdoctoral fellow He Jiankui announced that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies using CRISPR-Cas9, the ethical implications of using biomedical technology to conduct gene-editing experiments has been a topic of international controversy.

As part of the Arrow Lecture Series on Ethics and Leadership, Thursday’s talk emphasized the wide-ranging implications of CRISPR and the importance of responsibly testing and deploying gene-editing technologies.

Discovering CRISPR-Cas9

While the CRISPR-Cas9 system has gained notoriety in synthetic biology for genetic engineering applications, CRISPR is originally found in nature. Doudna’s innovation was leveraging the specificity of the natural system for targeted gene editing.

Doudna originally collaborated with UC Berkeley microbiology professor Jillian Banfield to investigate “unique bits” of virus DNA that Banfield had found in her bacterial cells.

Further investigation led Doudna to the Cas9 protein, which binds specifically to CRISPR RNA to alter gene sequences. Cas9 can recognize a twenty-letter sequence — an “address label” — to specifically target a region of the DNA sequence, making it a very precise tool.

“It is quite straightforward and conceptually trivial to use this protein and edit the genome,” Doudna said.

Doudna highlighted the diverse fields CRISPR technology has the potential to revolutionize. She mentioned researchers who optimized tomato crop yields through CRISPR techniques and others who have experimented on modifying animal organs for potential use as donor organs for humans.

“The diverse applications are an incredible demonstration of the power of a tool [like CRISPR] that allows you to have that amount of genetic control over an organism,” Doudna said.

Ethical implications

According to Doudna, there is a relatively low barrier to entry to CRISPR-Cas9 experimentation when compared to other gene-editing technologies. Scientists can obtain the RNA template needed in a few days by buying a starter kit that costs only $65, plus shipping. Doudna said the accessibility of CRISPR technology makes it “democratizing.”

“You don’t have to have money, or a lot of connections; you don’t have to know who knows somebody … to get a hold of [the technology],” she added.

But that accessibility has also made many people concerned about the developments in gene editing. In response to a question about the possibility of rogue states like North Korea obtaining and utilizing the technology to create genetically edited babies, Doudna emphasized the importance of working with regulatory agencies in an international effort to create regulations and control for dangers.

To this end, the editing of human embryos in Hong Kong “was sort of a wake-up call,” she said.

He Jiankui’s work on gene-editing human embryos — which has since been condemned by the Chinese government for violating state regulations — drew criticism due to the ethical implications of genetic manipulation.

Doudna has a unique perspective on the issue — He Jiankui sent her an email with the subject “Babies Born” before announcing his experiment to an audience at the second International Genome Editing Summit in Hong Kong. Doudna even met with the Chinese scientist several times — as did several Stanford researchers.

“He was naive about the public reaction to his work,” Doudna recalled. “He thought that he would be awarded prizes for his work, but in reality the reaction was quite the opposite.”

Doudna also believes the direction of research — particularly what the priorities should be — can become an ethical dilemma. She mentioned that there are often wealthy individuals and companies who want to sponsor research on rare diseases — the scientific community has to decide whether to value that, or to value research on the disease that has “the most pressing medical need.”

“Part of the path forward is education,” Doudna said. “It has to be about teaching young people about [gene-editing technology] — what it is, how it works and how to think about using it responsibly.”

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu and Yash Pershad at ypershad ‘at’ stanford.edu.