The Stanford Daily sat down with three members of Stanford staff — Dr. Emily Rabiner, Dr. Nancy Kollmann and Dr. Michaela Bronstein — to discuss their reading inclinations and how literature has shaped their lives. Rabiner is a lecturer in the French and Italian departments. Kollmann is a William H. Bonsall Professor of History, specializing in Russia and Eastern Europe, as well as the author of “Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Russia” and “Kinship and Politics: The Making of the Muscovite Political System.” Bronstein is an assistant professor in the English department and the author of the 2018 theoretical book “Out of Context: The Uses of Modernist Fiction.” This article is the second in a series of interviews with Stanford faculty about novels, journals and research materials.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What are your five favorite books on your bookshelf right now? What appeals to you about them?

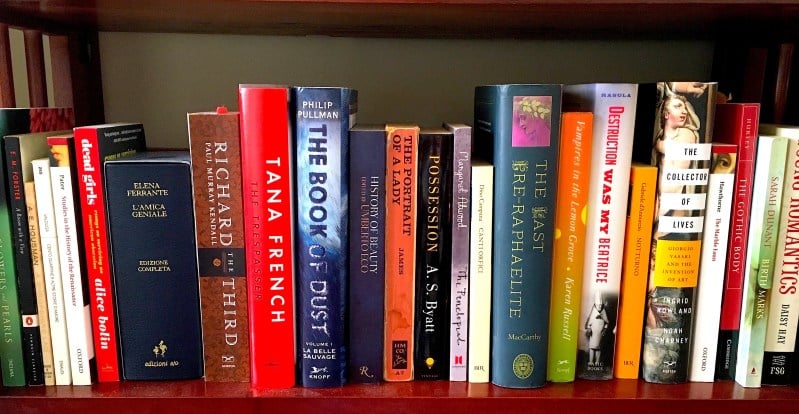

Emily Rabiner (ER): My five favorite books likely change on an hourly basis, but these stand out to me at the moment and represent some of the literary genres that most appeal to me: historical fiction (Ghermandi), creative retellings of canonical texts (Atwood), poetry (Campana), modernist prose (James) and detective fiction (French):

- Margaret Atwood, “The Penelopiad”

- Dino Campana, “Orphic Songs”

- Tana French, “The Trespasser”

- Gabriella Ghermandi, “The Queen of Flowers and Pearls”

- Henry James, “The Portrait of a Lady”

Nancy Kollmann (NK): I’m a historian, so I already read a lot in my day job! For relaxation, I look for contemporary novels that have strong characters and great writing that you can get immersed in. Interesting historical settings, or plots relevant to problems in our society today, also attract me. Recently, I enjoyed Daniel Mason’s “Winter Soldier,” Tommy Orange’s “There There,” Michael Ondaatje’s “Warlight,” Jesmyn Ward’s “Sing, Unburied, Sing,” Jennifer Egan’s “Manhattan Beach” and Mark Helprin’s “Paris in the Present Tense.” There’s also Amitav Ghosh’s great trilogy on the Opium Wars (“Sea of Poppies,” etc.). In anticipation of a trip to South Africa, I’m also reading classics by Nadine Gordimer and have a stack of books by contemporary South African writers that I haven’t yet read but look forward to.

Michaela Bronstein (MB): I think the question is: Which bookshelf? I’m an English professor, so my books (favorites and otherwise) are spread over more shelves than I can count, and I love almost all of them in different ways! The physical book I treat almost superstitiously is the copy of Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov” that I read when I was 16 — it’s the novel I love best, and I own it in multiple languages and editions, but whenever I’m moving, I always pack that copy last and unpack it first. I also have some 1920s Joseph Conrad volumes, including his epic “Nostromo,” from a collected edition that are printed on uniquely watermarked paper — if you hold it up to the light, you can see Conrad’s name around an anchor. Another favorite is a tiny paperback edition of James Baldwin’s “The First Next Time” from an early printing; it’s about the size of an index card, and I love to imagine a 1960s student activist carrying the book in a pocket. I have a delicate, tattered paperback of Virginia Woolf’s “The Waves” that I first read in high school — I think it may have been my father’s old copy, and it still has dozens of little post-it flags sticking out of it. (I didn’t used to write in books, so those faded flags are everywhere in the books I’ve had for a long time and usually remind me of what I noticed when I first read something.) And finally: the copy of Ngugi wa Thiongo’s “A Grain of Wheat” that I read in grad school changed the course of my research. I can’t imagine who I’d be as a scholar today if I hadn’t read it.

TSD: Have you ever failed to finish reading a book? Why?

ER: It’s rare that I don’t finish a book — the likelier event is that it takes me a long time to start reading something that I’ve been meaning to read — but I do read multiple books at once over the course of several months, putting one down for a few weeks (or even longer) before picking it up again. I often keep nonfiction, popular fiction and literary fiction in rotation, focusing on one or another depending on my mood.

NK: Very rarely — I’m a stubborn reader. But occasionally when a book seems to be going nowhere or [is] obvious in the plot or characters, I’ll set it down.

MB: It happens more often as I’ve gotten older — I think I just feel more forcefully how many other things I could be reading instead. One failure is Don DeLillo’s “White Noise.” Or maybe I went back and finished it? I don’t even really remember, so if I did finish it I probably shouldn’t have bothered.

TSD: Is there any movie or television adaptation that appealed to you more than the book on which it was based?

ER: There have been several, though two immediately come to mind. One is based in my field: Luchino Visconti’s film “Ossessione” is a 1943 adaptation of James M. Cain’s “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” The other is the recent television adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects.” I liked the novel quite a lot, but the series perhaps held a more visceral appeal for me.

NK: Can’t think of any.

MB: There are a few obvious answers — some classic movies like “The Godfather” are based on novels that are distinctly less enduring. To take an example where both book and film still have some lasting power, I do love Hitchcock’s film “Rebecca” more than the [Daphne] du Maurier novel. Then there are numerous works where I haven’t ever read the original, such as HBO’s recent miniseries “Big Little Lies.”

TSD: What’s one book (outside of your discipline) you often return to?

ER: I often return to Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber,” a collection of reimagined fairytales that she published in the late 1970s.

NK: I’m a historian (of Russia), so this work of literature is technically outside of my discipline — it’s Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina.” I’ve reread it twice after I first encountered it in college. It’s just breathtaking in its characters and evocation of Russian life [in the] mid-19th century.

MB: It would be cheating just to list literature in another language, right? I will say that the things I return to often have a tendency to become part of my work within my discipline — I read Camus’s philosophical essay “The Rebel” years ago, and somehow I’ve ended up writing about it in my next book.

TSD: What’s one book or series from your childhood that still impacts you today?

ER: I remember reading Philip Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” trilogy for the first time in middle school, but I have reread it many times in the subsequent years. Each time I return to it, the series gains new meaning and nuance for me. “The Book of Dust,” [Pullman’s] first entry in a new trilogy, was actually published while I was finishing graduate school, and I purchased it the day after I completed my dissertation.

NK: I read a lot as I was growing up, but I don’t recall anything especially strongly. When my children were growing up, though, we got hooked on reading aloud some of the more recent grand epics — CS Lewis’ “Narnia” books and Philip Pullman’s “Amber Spyglass” and [the accompanying] trilogy. That got me fascinated with dystopian and utopian literature, and I enjoy exploring that genre today.

MB: I suspect the things I read as a child impact me in ways I don’t even recognize. But I’ll go with “Calvin and Hobbes,” the comic by Bill Watterson. It’s about imaginative transformation, about how children play — the strip is constantly shifting back and forth between the “real” landscape of where Calvin lives (somewhere in the suburban Midwest, roughly) and the imaginative scenes he constructs (alien planets, etc.). For me, growing up in Seattle, the ordinary details of Calvin’s world — piles of dry autumn leaves to play in, endless snowy hills to sled down, streams in your own neighborhood to explore — were almost as distant as the things Calvin could imagine. I still think often about figuring out through “Calvin and Hobbes” that one person’s reality is another’s imagination.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Contact Claire Francis at claire97 ‘at’ stanford.edu.