The pin was vulgar beyond words — a grinning UC Berkeley bear, bent over what is meant to be an Indian, a half-clothed, black-braided man whose blobby shape resembles a Dino nugget.

This wasn’t vintage memorabilia, someone’s token from their college days back in the 60s when Stanford’s mascot was still the Indian. This shiny game-day pin was new.

That’s what unsettled Dahkota Brown ’20 the most this February after he spied it on the vest of a Cal tuba player. Brown, a member of the Miwok tribe in California, was in Berkeley for a basketball game as part of the Stanford Band, trading with the Band’s Cal counterparts for the mementos they stick on floppy white hats. The Cal tuba player — face reddening as Brown asked about the Indian pin’s story — explained to Brown that a UC Berkeley alumni group makes and distributes the baubles as the Big Game approaches.

Brown proposed a trade: his Aerosmith pin for the alumni handout. The Cal student quickly accepted.

“Afterwards, he told me that he actually felt like a cleaner person without it,” Brown said.

The pin was another addition to Brown’s collection of Native-depicting mascot items that he seeks to “take out of rotation”: pennants, T-shirts and other paraphernalia that he began accumulating back in high school, when he would face off on the football team against the Calaveras High Redskins. The Calaveras fans donned fake headdresses and war paint.

Yelling “Kill the Redskins” and “Scalp ’em,” the home crowd didn’t feel so supportive.

—

The same month that he encountered that Stanford Indian pin, Brown was named the Stanford Tree. For the next year, he would dance in a homemade leafy costume at games as the University’s unofficial but beloved mascot. As the first Native student to win the title of Tree, Brown is cognizant of how his new role resonates with school history. This history helped motivate his run. The slogan of his bid for Tree was a joking imperative: “Make the mascot Indian again.”

Brown’s reclaiming of the Indian mascot is the latest in the old emblem’s evolution at Stanford — its rise, its removal in the early 70s and its resilience on the fringe.

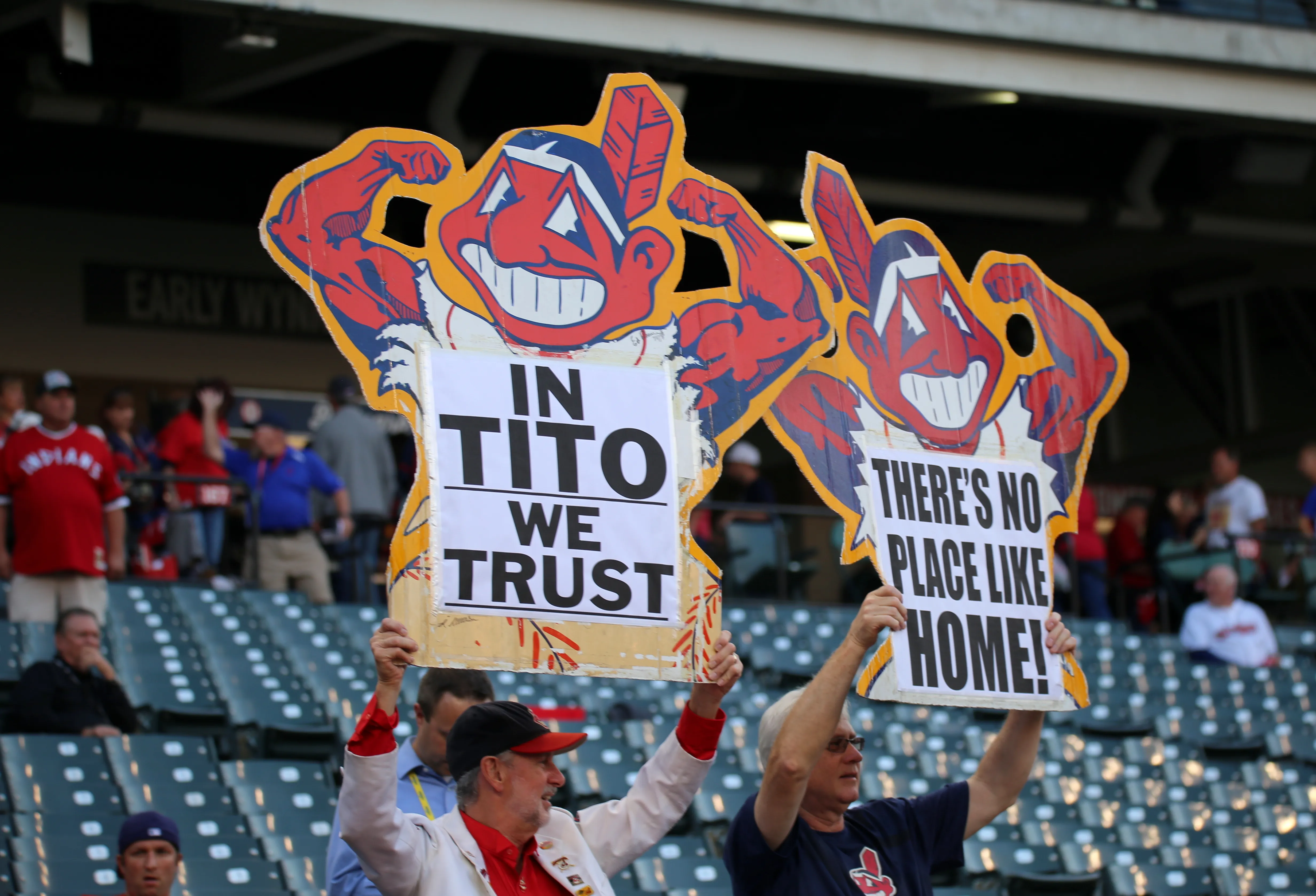

Stanford is often cited as the first Indians sports team in the country, either school or pro, to completely disavow its name. As a movement stirred, some institutions followed quickly: Dartmouth, for example, removed its Indian nickname and mascot only two years after Stanford, in 1974. Other teams held on to their branding for decades. The Cleveland Indians retired their controversial Chief Wahoo icon just this year amid pressure from protestors and Major League Baseball as well as a competing campaign to #KeepTheChief.

The story of Stanford’s Indian mascot is in many ways one of swift, progressive shifts. It’s a story of student activism that made quick gains with quiet tactics in an era of bitter confrontations between protestors and school administrators.

But Stanford’s mascot is also a story of resistance to change: of love for tradition, of opposition both predictable and unexpected, of a racial caricature that keeps popping back up and a dispute about Native American representation playing out around the country. Franchises and student teams — Washington Redskins and Calaveras Highs alike — continue to divide, and one analysis from a few years ago estimated 2,000 Indian mascots remaining in the U.S.

“We used to be the Indians, and now there’s a Native student who is the mascot,” Brown said. “Kind of ironic, kind of funny, but there’s still a very serious issue that lays underneath it all.”

The Stanford Indians

The Stanford Indian was a belated addition to the University’s identity, officially adopted by student government in 1930 some 45 years after Stanford’s founding. The Indian name grew in prominence under star football coach Pop Warner. “FUTURE MEMBER OF INDIAN TEAM SIGNS UP EARLY,” a Daily headline from 1931 declared. A seven-year-old boy named John Williams had already pledged to play for “the Big Red Machine.”

Stanford’s new moniker was an echo of Warner’s early coaching career. Before Stanford, he headed up the nationally competitive football team at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which became the model for a host of boarding schools built to assimilate Native Americans into white culture (“I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked,” Carlisle’s founder once said). The Carlisle team was called the Indians.

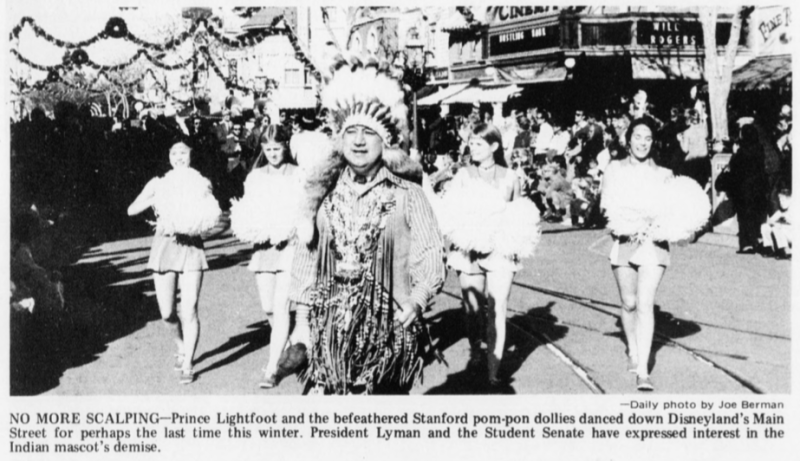

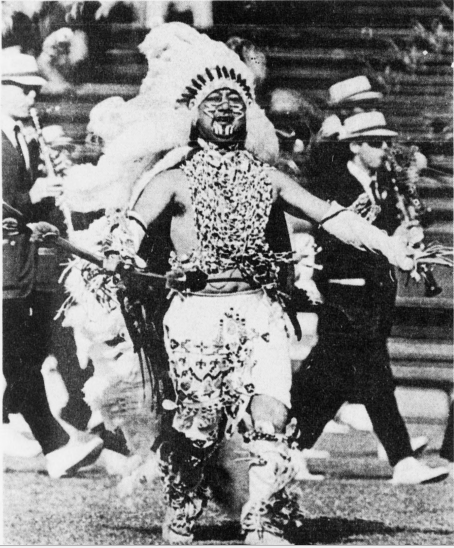

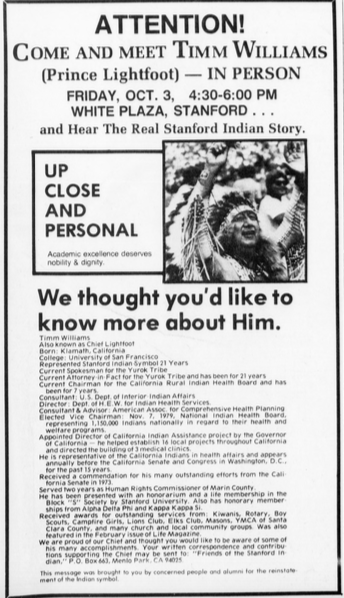

The Stanford Indian may have taken root late, but it would become a ubiquitous — and crowd-pleasing — part of Stanford’s identity. The mascot gained star-power thanks to the odd devotion of a man with no connection to the University: Timm Williams, known to fans as “Prince Lightfoot” or “Chief Lightfoot.” Starting in 1952, Williams spent 20 years as the live incarnation of Stanford’s mascot, chanting and dancing at halftime in a headdress and casting hexes on the Indians’ athletic foes.

Williams was a polarizing figure. He was a Yurok Indian from northern California, a leader-spokesperson for his tribe, who pushed for Native American rights and served briefly as Governor Ronald Reagan’s advisor on Indian affairs (he was fired months after Stanford renounced its mascot). But Williams also eventually found himself pitted against fellow Native Americans who felt that his performances demeaned their cultures.

He showed uncommon devotion to Stanford sports, so loath to miss a home game that he once showed up to dance while recovering from the flu. But he had no alumni or employee ties to the school. No one gave him money; Prince Lightfoot was largely his brainchild and his prerogative. He even paid for his feathered costume and, for a while, his travel to keep up with the teams.

“I have a real feeling for Stanford — it is a great school with great students,” Williams told The Daily 15 years into his mascot tenure. “I like to think, too, that the students appreciate my being at the games.”

Prince Lightfoot wasn’t always controversial. For many, he was beloved. By the late 50s, the mascot even had his own weekly TV show on which he danced, told legends and showed crafts, all in full costume while the Stanford Band played his theme song.

Hal Mickelson ’71 was in the Band as a student, and the Band spent a lot of time with Williams. Mickelson would narrate over the PA system during halftime as Williams performed (“And now Prince Lightfoot will put his hex on the Trojans of USC…”). Mickelson, who visited Williams up in his Crescent City home after graduating, recalled a man whom Band members admired and learned from.

Loyal to his friends and to the University, Williams would come to feel abandoned by Stanford.

‘We were all horrified’

Elissa Patadal ’74, one of the Native students who successfully campaigned against Stanford’s mascot, had barely heard of Stanford when she applied; she thought it was in the Ivy League. So, Stanford’s mascot came as a surprise. About to leave for freshman year, Patadal was watching a Stanford football game in the living room with her family when Prince Lightfoot came out to entertain.

“We were all horrified and terribly embarrassed,” Patadal said. The Prince’s dance was all wrong.

Patadal and her family weren’t the only new Stanford community members who balked at the mascot. A recent push to recruit minority students had brought more Native students to Stanford than ever before in 1970 — that fall, over 20 of them entered a school that five years ago had enrolled a single Native student across all grades. Many of these new arrivals on the Farm saw Prince Lightfoot’s performances as a mockery, a stereotype-laden mishmash of traditions that weren’t all Williams’ to draw on. To them, the “hexes” turned tribal religion into play; the mouth-slapping “woo-woo” sounds were offensive; Williams’ Sioux-style feather headdress was out of place on a Yurok.

Feathers are earned through worthy acts, says Dean Chavers MA ’73 ’75 Ph.D. ’76, a Native graduate student who arrived the same year as Patadal. In all his life, Chavers has been bestowed two feathers — gifts from people who thought his activism was “badass.”

Timm Williams was out on the football field sporting feathers in the hundreds.

“Timm, let’s have some pride here,” Chavers recalls appealing to Williams in a meeting between the man behind Prince Lightfoot and the new Native students, who had just formed the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) and would gather every Sunday in a frame house near the Law School. According to Chavers, the students extracted a promise from Williams that he’d cut out certain aspects of his performance, like the hexes.

But the next football game rolled around, Chavers said, and nothing had changed.

“We went to every home game for all the years we were there, and it was just degrading to watch him out there doing his silly thing,” he said.

Williams and the founders of SAIO had opposite views on what Stanford’s mascot meant for Native Americans. Williams argued that serving as Stanford’s mascot was an honor, something that would elevate Native culture in the public eye. He stuck by this reasoning years after the Indian mascot’s removal, at a 1980 talk on campus that drew mostly yellow-arm-banded opponents — the latest of increasingly implausible attempts to resurrect an issue that University administration had declared closed. Stanford’s Indian was a symbol of courage, Williams insisted at that 1980 gathering.

“We don’t need people shutting us out and forgetting about us,” he told the crowd, adding strangely, “An American Indian would rather be kicked than forgotten.”

Williams found others to back him up in his positive view of the Indian mascot’s impact. A fellow leader in Yurok tribe, Dorothy Haberman, wrote scathingly of the SAIO students in 1972, saying that they are “evidently ashamed of their beautiful Indian blood” and that if they disliked the mascot so much, perhaps they should go find another school. The Native community both within and without Stanford was divided, particularly because of Williams’ role — 107 members of William’s Klamath River Yurok group signed a letter urging the Indian mascot’s preservation.

“We feel, as Indians, we are being crucified by our very own,” Haberman wrote.

A national dispute

Today, supporters of Indian mascots in sports point to a Washington Post poll that found nine out of 10 Native Americans say they aren’t offended by the name of the Washington Redskins, whose owner Daniel Snyder has resisted calls for the nearly $3 billion franchise to rebrand (“We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple,” he told USA Today. “NEVER. You can use caps”). That nine out of 10 statistic means that Native opinion hasn’t changed much since 2004, when the Annenberg Public Policy Center conducted a similar survey.

“I’m proud of being Native American and of the Redskins,” a Chippewa teacher from South Dakota told The Post in 2016. “I’m not ashamed of that at all. I like that name.”

Still others echoed Timm Williams’ argument about raising Native Americans’ national profile, or told The Post they simply didn’t care. “The name is nothing to me,” one man said.

When the NCAA pushed member schools to review potentially offensive mascots in 2005, ultimately banning the Indian, it gave exemptions to several teams that secured the blessing of the Native tribes they were named after. The Utah Utes, Central Michigan Chippewas, Florida State Seminoles and Mississippi College Choctaws all argued that they could use the Indian mascot inoffensively.

“That the NCAA would now label our close bond with the Seminole people as culturally ‘hostile and abusive’ is both outrageous and insulting,” Florida State president T.K. Wetherell said. He threatened legal action before his school was granted an exemption.

These schools say they’ve worked with tribes to encourage more thoughtful use of their mascots and avoid denigrating or mischaracterizing Native communities. Citing the input of the Saginaw Chippewa Chief, Central Michigan University urges fans not to use imitative chants or face stripes (the Chippewas have roots as hunter-gatherers who wore war paint only in rare circumstances).

Indian mascot critics, on the other hand, contend that something offensive to even a minority of Native Americans should be dropped. They also cite a growing base of research on racial representation and the psychological effects of Indians’ portrayals in popular culture.

The American Psychological Association issued a statement against Indian mascots in 2005, citing scientific studies. More findings have followed since asserting that such mascots reinforce racial stereotypes — not in a way that study participants admitted to, but implicitly, in a way that emerged through their mental associations. In a set of studies published in 2008, a team of researchers — two of them Stanford-based, another a Stanford alum — found that Native students’ self-esteem, esteem for their communities and ability to imagine achievement-oriented “possible selves” were all lower after exposure to Indian mascot images.

When European Americans were shown Indian mascots in a different study, they reported higher self-esteem than participants shown a control image or an image of the “Fighting Irish.”

“[Indian mascots are] actually making white students feel better about themselves, which to me is an even more dramatic problem,” said Adrienne Keene ’07, a Cherokee Nation citizen and Assistant Professor of American Studies and Ethnic Studies at Brown University.

Keene, who’s written about mascots on her blog “Native Appropriations,” has become a prominent voice pushing back on misrepresentations of Native Americans. Her Twitter account @NativeApprops has over 65,000 followers.

Despite the opinion polls touted by Redskins fans, Keene thinks the movement against Indian mascots has made headway recently, eroding the “myth” of the often cartoonish depictions as honoring a culture.

And this movement gained an early victory at Stanford.

‘The right thing to do’

The early 1970s was no quiet time at Stanford. Opposition to the Vietnam War had galvanized students to bolder action and more open confrontation with their school administration than ever before. The same school year that Chavers and his fellow Native students arrived, a protest against ROTC’s presence on campus devolved into four hours of chaos as students hurled rocks and police unleashed tear gas. A sit-in the next year left dozens injured and $100,000 in damages. Unrest was the norm.

As one Daily columnist reflected in 1975, you could almost miss the Indian mascot’s removal amid all the drama.

But for Bill Stone ’67 MBA ’69 — then an assistant to University President Richard Lyman in a Quad Building 10 newly outfitted with shatter-resistant glass windows — the Native students pushing for a new mascot stood out all the more for their muted tactics. Stone has forgotten many details of that era now, but he can still recount how the students crowded politely into the administration’s lobby area for one of their visits, waiting to make their case to the president. He was used to getting calls from the police chief during lunchtime about activists bearing down on the office from White Plaza: “they’ll be there soon,” the chief would warn.

“They didn’t come and pound on the doors like many student protests at the time,” Stone said of the SAIO students. “They made an appointment.”

The students’ arguments were convincing and their goals straightforward, he said. “It was the right thing to do.”

But Chavers says President Lyman was not immediately receptive to the students’ agenda, which focused on the mascot but sought more broadly to carve out a stronger place for Native cultures at Stanford. In their first meeting the fall of 1970, he recalled, Patadal asked Lyman about Indian Studies classes — to which Chavers remembers Lyman saying something like, “If an Indian student comes to Stanford, he has to come on the same terms and conditions as all other students.” The Native American Studies program at Stanford wasn’t founded until 1996, long after its peer UC Berkeley launched a program in 1969.

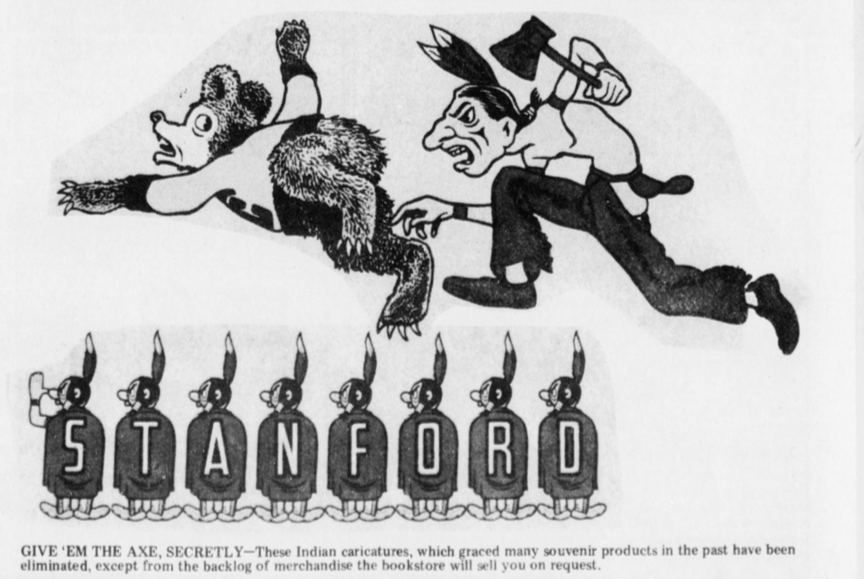

Lyman writes about his change of heart on the mascot issues in a letter to alumni explaining the Indian’s removal. Initially, he thought the move extreme — why not just revise the mascot? And at first, that’s what Stanford did, ditching its traditional cartoon depiction of the Indian. The Bookstore stopped ordering items with a bulbous-nosed caricature, opting instead for what the University deemed a more “dignified” chief. However, to many Native students’ disappointment, the stocked up merchandise was still available by request.

Even the incremental change from cartoon to solemn profile left some bewildered.

“I’m dumbfounded,” a rep for Governor Time Co. told The Daily after the paper declined an ad for its newly designed Stanford Indian wristwatch. They hadn’t gotten the memo about the mascot’s new look. “We thought that was the Stanford Indian,” the representative added. “This is new to us.”

The student government was also instructed to redesign its paychecks, which featured 10 miniature Indians thumbing their noses.

The next school year, in 1972, 55 Native students signed a petition calling for the Indian mascot to be removed altogether. Even the revised image of the Stanford Indian did their race a disservice, they said.

“People will fail to understand the human side of being Indian,” the petition asserted, “as long as they can choose instead to see only the entertaining aspects of Indian life.”

The petition went to University Ombudsman Lois Amsterdam, who lent her support in a memo to the president.

“Stanford’s continued use of the Indian symbol… brings up to visibility a painful lack of sensitivity and awareness on the part of the University,” she wrote, urging the mascot’s immediate disavowal.

Local and state groups who heard about the motion wrote in with their endorsements. Within a few months, student government had voted 18-4 to drop the Indian, and in April of 1971, Lyman put his authority behind the mascot’s abolishment.

‘Draconian decision’

In her memo to Lyman, Ombudsman Amsterdam was optimistic about Stanford alums’ willingness to leave the Indian mascot behind. Alumni devotion to the school is much deeper than a symbol, she argued: “Surely we do not expect less from our alumni than we do from ourselves; and we should not disparage the alumni by assuming that they would cling obstinately to a symbol of the past whose present inappropriateness has become plainly apparent.”

Some alumni did accept the transition without protest. Others lauded the decision. But still others clung — fiercely. And opposition to a move questioned as “political correctness” came from more than just nostalgic graduates.

For students like Charlie Hoffman ’73 MBA ’76, a former Daily staffer, Lyman’s edict on the mascot was an outrage — not for its shedding of tradition, but for the undemocratic way it changed the face of the school. These days, Hoffman believes the school was right to phase out the Indian. But back then, the mascot question quickly became tangled up in broader resentment toward University politics.

“This was a draconian decision rammed down the students’ throats,” Hoffman said. “Boom, the Indian mascot was gone … In an era where students were trying to have their voice, it was another instance of the University [acting] really, at the end of the day, all-powerful.”

Lyman anticipated the need for some sort of broader input on such a controversial decision, his ex-assistant Stone said, even though administrators and SAIO members argued that representing a race respectfully shouldn’t be a matter of majority-rule. The school formed a committee, which dutifully included representatives from the alumni crowd in an effort to “allow groups … to feel they have been consulted,” as The Daily paraphrased Stone back in 1972.

But diehard Indian fans on the group would later complain that the decision had been made from the start. Despite the decisive vote in student government, nearly 60 percent of the student body as a whole voted to keep the Indian, and a majority of the mail that deluged Stone in the president’s office advocated the same.

Foremost among the mail-senders: alumni. The Buck Club, Stanford’s athletic booster group run by alums, passed a resolution in favor of the Indian, and letters to the administration threatened withheld donations.

“It’s not going to close the school,” the fundraising office told Stone when he queried them.

Certain alumni had already been watching with displeasure as Stanford’s student body became more activist, more liberal, more racially and culturally diverse. Stone recalls laments that Stanford “had been taken over by Communists.” For these critics, the mascot’s removal was further proof of the University’s wayward bent — part of a bigger frustration with Stanford’s trajectory. The Indian issue pervaded the newsletters of one right-leaning alumni group called the New Founders League, even though restoration of the mascot was never one of the organization’s official goals (the League’s 800 members sought everything from ROTC’s reinstatement on campus to an end to affirmative action admissions).

“In terms of alumni support [for the league], there is nothing that has brought out support anywhere near that for the Indian,” Lowell Berry ’24 told The Daily in 1977, five years after the mascot was nixed. “Some of our people would like to drop the Indian issue, but with the support as great as it is, we would be doing our supporters a disservice to ignore it.”

Around that time, Stone became president of the Stanford Alumni Association, and he remembers a distinct weariness in his predecessor toward the challenge of reconciling Stanford’s past and present. Backlash over the mascot change was one symptom of something larger; Stanford, like the rest of the country, was changing rapidly, in ways that some people would never be comfortable with.

The former Alumni Association president “was tired of spending all the time arguing,” Stone said.

The Tree came about as Stanford struggled to settle on an official replacement to the Indian and as a 1975 Daily poll of the student body failed to find consensus. The Band debuted a Tree mascot in jest at that year’s Big Game, having narrowly voted down competitors “Holy Order of Fries” and “Steaming Manhole Covers.” But the Tree stuck. Today it remains the emblem of the Band rather than the University, which reverted to its original moniker the Cardinal.

During all the mascot confusion and even after its resolution, the Stanford Indian persisted in unofficial ways: on T-shirts and Big Game paraphernalia, in defiant newspaper ads and opinion columns.

Years after the Indian’s abolishment in 1972, the Friends of the Stanford Indian was registered as a new student group, while an outside-campus organization of the same name claimed over 2,000 members. The Stanford Band manager complained to The Daily that the Friends’ leader — a Palo Alto insurance executive who bore no formal ties to the University — had tried to offer him money to put the new Tree mascot aside. Meanwhile, the Indian’s most ardent supporters were vindicated when, in the late 70s, Timm Williams snuck back onto the football field to cheers and the war chant drumbeat of the Band.

The University did move to sideline Williams, telling campus police not to let him in the stadium. But that didn’t stop another man in traditional Native American regalia, a member of the Nez Perce tribe invited by alumni, from riding a horse onto the field using a fake pass that police traced back to the Friends of the Stanford Indian.

It didn’t stop people from writing in to the school, hopeful that their mascot would return. “I am still answering letters from alumni asking when the Indian will come back,” Director of University Relations Ron Carlson said in 1985.

And it didn’t stop an alumnus in 1989 from marketing watches, buttons and more bearing a cross-eyed, cross-looking Indian man. He argued that the mascot didn’t have to be divisive.

“Old alums should have a right to be nostalgic,” Robert Fuller ’60 said at the time. “[The Indians] existed at one point. My attitude is that there isn’t anything racial about it. If I thought there was, I’d stop doing it.”

A ‘dead issue’?

In 2012, 40 years after President Lyman’s administration declared the Stanford Indian a “dead issue,” Class of ‘07 graduate Keene spotted the Indian’s cartoon figure at her five-year homecoming reunion.

She saw it stickered on a traffic cone. On the matching outfits of two different couples. On the white shirt of an undergraduate student who posed for her camera. She saw it right as she arrived on campus, on pins proudly worn by members of the Class of 1962 — fastened to an elderly man’s hat, to a woman’s name tag. “Class of ’62 Reunion — Skin the ‘Cats,” the pins read, a reference to a rival mascot. They showed a naked mountain lion shivering while a cross-eyed, hatchet-wielding Indian in a loincloth holds up its bloody skin.

There was nothing honoring Native Americans in this mascot, Keene thought.

“It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, my grandpa went to Stanford and I pulled this out of the basement,’” Keene says.

As someone who helped to plan the reunion, Keene had been heartened to read the Stanford Alumni Association’s rules on the old mascot in her training packet, which emphasized that the Indian was hurtful even if “not meant to be offensive when adopted.” The Stanford Alumni Association does not “fund, use, distribute or condone officials mailings, memorabilia or activities that use the Indian mascot,” Victor Madrigal ’94, director of alumni and student class outreach, wrote in an email to The Daily.

And yet, according to an email about the Indian pins sent to 2012 reunion organizers, someone had found the pins at a class check-in table. With the Class of ’62, at least, the Alumni Association’s guidance on mascots either hadn’t gotten through or hadn’t been heeded.

Madrigal did not say specifically how the SAA handled the incident, only that it continues to make volunteers aware of the mascot policy. The Class of ’62 pins would never be made or given out with the Alumni Association’s consent, he added. (Class representatives did not respond to a request for comment, nor did they respond to Keene when she contacted them back in 2012).

“On rare occasions we have had to address isolated situations,” Madrigal said.

Stanford Indian gear is not common these days. Still, Mickelson, the former Band announcer, swears he can find an Indian sweater, scarf or necktie within 10 minutes amid the tailgate parties at any home game. He hypothesizes that for some alumni, wearing Indian paraphernalia is an act of defiance, “to kind of show that you can’t control ‘em.” But he also understands the devotion that many feel to a tradition.

“There were Stanford fans who were prepared to have Stanford Indians license plates on their cars and markers on their gravestones because they identified so strongly with the team,” he said, recalling fans’ reactions to losing the mascot.

The same month as her 2012 reunion homecoming — the one where she saw so many contemporary tributes to the Indian — Keene received an email from one of her friends on campus, forwarded from a student in the Class of 2014. It was an order form circulating on Stanford chat lists. Stanford Indian apparel was in high demand.

“To meet the overwhelming desire of, well…everyone, I am starting the process to make a new batch of those magnificent Stanford Indian Sweaters that people won’t shut up about,” began the email from Nick Hoversten ’14.

Hoversten says he was a “naive 20-year-old who thought that throwback Stanford Indian sweaters would be cool.” He didn’t get “what the big deal was.” After an initial batch of just 10 or so sweaters piqued both student and alumni interest, Hoversten planned to scale up to 60 for his second order.

He never completed it.

Carly Kohler ’13, a student vocal against the Indian mascot, messaged Hoversten over Facebook. At first, Hoversten says, he went on the defensive, explaining why he didn’t think he’d done anything wrong. But then Kohler explained that she just wanted to hear his side.

“Looking back, I think my initial response of entrenching and becoming defensive is unfortunately typical of what we see happen in these scenarios,” Hoversten said. “What wasn’t exactly typical though, was Carly’s response to that initial response. She was understanding and compassionate, and that allowed us to have a conversation rather than a shouting match — and I ended up learning a lot from her.”

Hoversten and Kohler’s Facebook conversation turned into a lunch. Hoversten went to a meeting of local Native American leaders. Alongside Kohler, he gave talks to Stanford’s Greek community about what they’d discussed — and about why he was wrong to send out the cavalier sweater form, even if he didn’t mean to hurt anyone.

“If I had known how they would affect others,” Hoversten said, “I definitely wouldn’t have made the same decision.”

Growing awareness

Brown, the new Tree, had a tedious but time-honored task this summer: sewing the costume he’ll dance in for the rest of the year. Every Tree makes their own outfit, and while a friend welded the metal frame together, the rest is up to Brown. Each leaf of cloth-sheathed Styrofoam takes him over half an hour to make, he said; he’s hoping to have 70 by the end of the summer.

His favorite leaf so far is cut from a shirt mailed to him by Steven Paul Judd, a prominent Native American artist. Earlier this year, Brown posted an open call for fabrics and designs from the Native community that he could highlight in his creation. Judd responded with “his take on the Incredible Hulk,” Brown explained. The T-shirt he sent shows a Native person reading a newspaper article about a treaty being broken, prompting his transformation into the “Indigenous Hulk.”

Brown has spoken out against Native mascots for a long time, starting in high school. His local advocacy led him to speak in Washington, D.C. on the issue and testify before the California State Assembly for the California Racial Mascots Act, which banned public schools from playing as the Redskins.

Just as Stanford led the way in abolishing Indian mascots, California became the first state to enact such a law. The handful of schools affected have been slow to fully phase out their mascots, the Daily Cal reported last fall, and some school officials remain openly disdainful of the change and what they see as the overreaction of a uptight society. The legislation also does not attempt to regulate less commonly condemned team identities like “Indians” and “Braves.” But for the guy who used to listen to the home fans shout “Scalp ‘em,” it’s still a big victory.

The Racial Mascots Act provides “an opportunity for Native youth to obtain an education free from mockery,” Brown said in 2015 after the law was signed into effect.

Brown’s work on Indian mascots, college access and other issues has made him something of a “superstar” in the Native education sphere, said Keene. She sees Brown’s new role as a testament to how far Stanford has come since the days when Timm Williams’ hex-casting Indian was the University’s dominant representation of Native Americans.

“I think it’s really powerful and kind of cool,” Keene says, “that we used to have Prince Lightfoot, quote-unquote ‘dancing’ around the football game — this Native guy in a fake Indian costume playing to the crowd and playing into those stereotypes — and now we have Dahkota, who is a proud contemporary Native person … embodying all of the subversive and irreverent things about being a Stanford Tree.”

Brown hopes to leverage the Tree role to push back on continued use of the Stanford Indian. He’s thinking of making some sort of announcement with the authority of the mascot behind it.

“Like right at the beginning of football season, publishing something as the Tree saying I’m not going to pose for pictures or anything if you’re wearing Stanford Indians gear,” Brown explained. “Just so people are aware.”

Already, the Band is part of an annual “Defend Our Honor” campaign organized by the Stanford American Indian Organization, the group that Chavers and his fellow Native students founded back in 1971. Every year around homecoming, as alumni flock to campus, SAIO distributes shirts meant to focus attention on why the Indian mascot is problematic.

Keene noticed the Band’s show of unity in wearing Defend Our Honor shirts when she was back at Stanford for another Class of ‘07 reunion, this time in 2017.

“It’s not something I think we’d have seen 10 years ago, five years ago,” she said.

Keene is glad the University takes a clear stance on the mascot but wishes that it wasn’t always Native students bringing use of the old mascot to people’s attention. It would be nice, she says, if “other folks could hop in and do that labor,” too.

Still, she thinks she’s seen less of the Indian mascot in recent years. Something, she said, seems to be working.

Meanwhile, another issue has drawn the Stanford Native community’s attention as the University struggles with whether to rename campus buildings and the street of Stanford’s address, erasing references to Junipero Serra. Serra, a newly-sainted Catholic priest, was behind the California mission system that devastated Native tribes. After years of debate and protest among students, and a University committee so hung it had to be disbanded, Stanford announced in September that it would rename two buildings and seek to change its address.

The move to drop Serra’s name, just like the decision to drop the Indian mascot, is largely the work of Native student-led activism. The conversation around renaming strikes at many of the mascot debate’s core issues, with dueling charges of politically correct revisionism and disrespect to an entire people — one more way that, despite the University administration’s assertions back in 1972, the Stanford Indian controversy is diminished but never quite dead.

Contact Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Olivia Mitchel contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: The online version of this article has been updated to reflect the University’s recent announcement that two buildings named for Father Junipero Serra will be renamed. Because the announcement came after our print publishing deadline, this information was omitted from the print version.