In recent memory, has there been a more inspiring week for film? Think on it: Malick’s latest joint, Studio Ghibli is back, Kristen Stewart fights texting ghosts (and herself), and James Baldwin goes to the movies. All of these were released in the past week or two—not to mention the still-playing “Get Out,” “La La Land,” “Moonlight,” “The Salesman,” “Hidden Figures,” “After the Storm,” “Raw,” and the cat movie. Here’s a quick scan of this unusually rich week of cinema:

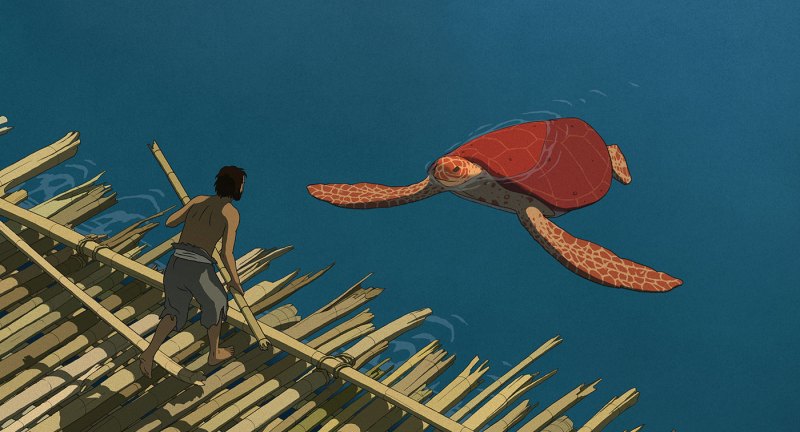

“The Red Turtle” (directed by Michaël Dudok de Wit)

This French animated tearjerker bowled me over the most, by which I mean I bawled. The Japanese bastion of great film art, Studio Ghibli, co-produced this haunting gem, about a sailor stranded on a desert island and his encounters with the uncaring flora and unique fauna (the titular tortoise). Only one English word (“Hey!”) is screamed, so it’s essentially a silent film. All the better—to place us in a more patient, attentive mood.

Dutch writer-director Michaël Dudok de Wit has crafted an existential fairy-tale about family, love, death, nature’s shocking neutrality, human cruelty, growing old, and what the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi saw as mankind’s cicada syndrome—our inability to stretch our minds beyond our own tiny scale. Ghibli director Isao Takahata (“Tale of the Princess Kaguya,” “Only Yesterday”) served as “artistic producer” for this venture, and in a way, it functions as a sister film to Takahata’s moving World War II melodrama “Grave of the Fireflies” (1988). Takahata’s aesthetic is writ large in every one of de Wit’s minimalist cels, delicate/devastating string cues, and oscillations between concrete plot and abstract atmosphere. We are asked to observe the grainy smoothness of sand and endless, still horizons—how that blue heaven in the sea can swallow us up without a taste. It’s skimpy on “character” because it’s explicitly a fable—and one of immense beauty. 80 minutes.

“Personal Shopper” (directed by Olivier Assayas)

This Kristen Stewart-led pseudo-horror from Olivier Assayas is both an effective thriller and a smart deflation of its own non-logic, of the virtual emotions conjured up by movies. Stewart hates her job as the personal shopper of a high-profile celeb model, she wants to escape Paris, but she can’t because she’s a medium trying one last time to contact the spirit of her dead twin brother Lewis. Like Deborah Kerr in “The Innocents,” Stewart has nobody to corroborate her story of paranormal activity. She is utterly alone, fighting against the spirits of a ghostly underworld, her own self and her/our ever-mounting schizoid terror.

“Personal Shopper”‘s not-cliché hauntedness doesn’t just stay in the theater; it stalks us back to our beds. Assayas is working through one of the still-unsung masters of silent movies, the French director Louis Feuillade, who birthed the modern-day paranoid thriller, where an ordinary landscape hides a vast conspiracy. Feuillade’s trippy, proto-TV serials (“Fantomas,” “Judex,” “Les Vampires”) used “normal” Parisian buildings as the perfect backdrop to channel abstract fear in the modern world: abstracted through networks of masked madmen and venomous vamps. Assayas transposes that always-being-watched creepiness (which our civilized selves must constantly work to ignore) into the 2010s: iPhones as the new (un-)normal. Like Feuillade, Assayas suggests these bumps-in-the-night—signs we tell ourselves mean something—might just be in our head. But are they? We’re hoodwinked time and again by Assayas/Stewart, by virtual screens, by not-there illusions (by cinema!). Our senses run faster than our brain—and yet we don’t mind the hoodwinking. 110 minutes.

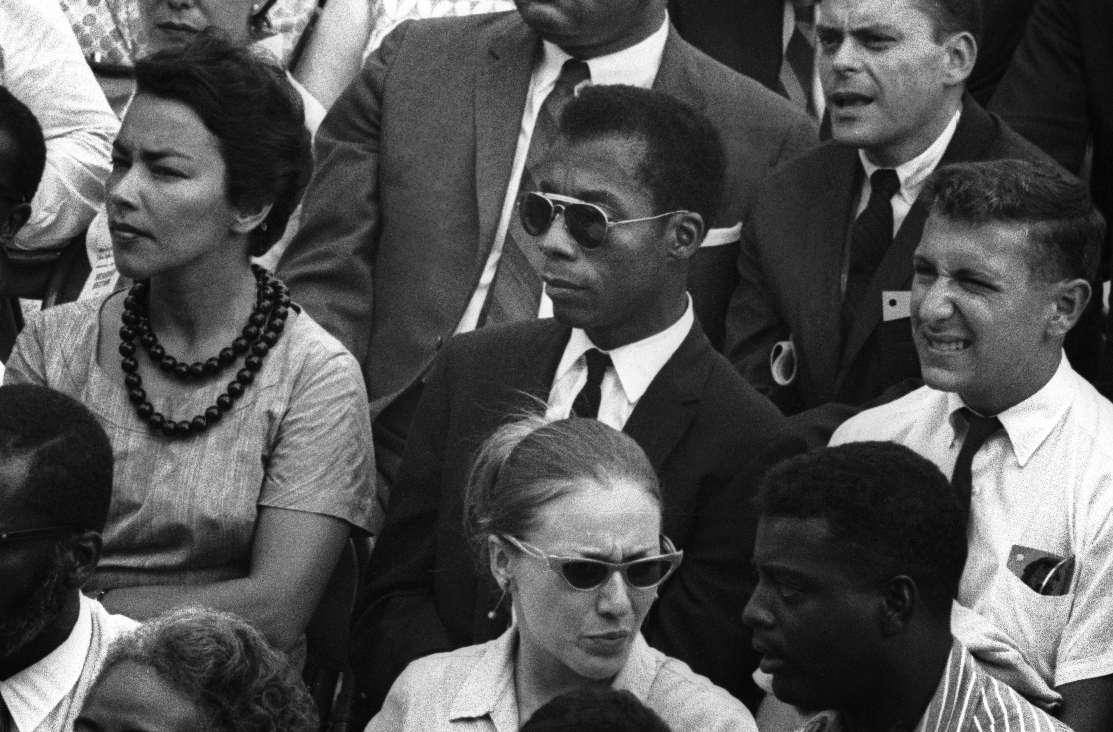

“I Am Not Your Negro” (directed by Raoul Peck)

Through the words of James Baldwin, Raoul Peck recreates the shouting-match of 20th century American history. He uses key texts by Baldwin as a starting-point: “The Fire Next Time,” “The Devil Finds Work” (Baldwin’s excellent dissection of race in American cinema), and the notes for an unfinished novel that would have traced modern Black history through the lives of Dr. King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers.

“I Am Not Your Negro” provides a rich model for how to more explicitly integrate questions of race into 21st century documentary forms.. Peck’s film shows how a meandering, jump-from-one-topic-to-the-next tone (the Peter Watkins approach) is needed in the best documentary cinema. His doc pays tribute to American film criticism in its striking series of clips, grappling with the history of American movies (i.e., the history of American racism), of erratic back-and-forths: from Sidney Poitier uplift to Stepin Fetchit shame.

“I Am Not Your Negro” is part of a larger artistic effort to understand the place of words, Truth, and acts of social dissent, now. It has a remarkable fluidity that proves how documentaries, when done with guts and boldness, give art the tools to enact social change. 90 minutes.

“Song to Song” (directed by Terrence Malick)

I wouldn’t be surprised if Terrence Malick’s “Song to Song” ended up being my favorite of his post-“Tree of Life” experimental work. I say that since it’s the one I struggled hardest to enjoy—and that’s, I think, a good sign. For the first two hours, I was sighing deeply and tapping my feet, feeling every second of the second hour. I worried that Malick had finally gone off the deep end into his own murky funk—but then! for the final half-hour, I was bolted to my seat, tracing the steps which led to my sudden love for what seemed like a self-indulgent boor.

“Song to Song” is something of a postscript to the first Malick work from last year, “Knight of Cups,” which derived its boldness from expansiveness. “Cups” dealt with the history of cinema, of Los Angeles, and of Malick’s family background, all filtered through a dense web of references from movie, literature, and philosophy. By contrast, the focus of “Song to Song” is much smaller: the increasingly mind-numbing sexploits of two musician gonna-be’s (The Great Gosling and Drab Fassbender), trying to figure out at what point in their coke-fueled affairs, orgies, betrayals did they stray off the cosmic art path. Michael plays God with women, treating them as heaps of meat and sex-dolls in ways that make your skin crawl; Ryan almost gets there, but Rooney Mara (MVP) asserts her presence and helps Ryan (more importantly, herself) see the spirituality s/he’s missing.

It starts off as a scurrying send-up of Late Malick. A volley of techniques is deployed: hoary fish-eye lens, sleek “Point Blank” apartments for savage Rooney-Ryan sex (50 shades of hate), the camera’s nose turned toward the Sun, five ring-around-the-rosie narrators, every third shot is an actor twerking or jumping up-and-down in mock mania. (Malick loves to choose his actors’ least appealing, most artificial moments—most human?) All this busyness stiffens Malick’s hard-earned new cine-language.

But suddenly, almost like a miracle, “Song to Song” ditches the melodramatic and flat Fassbender narrative (the real thorn and the less interesting thread) and achieves a stunning coup de cinéma, soaring along with Rooney and Ryan finding love and meaning with the fury and frenzy of Malick’s previous 2010s films (“To the Tree of Cups in Time”).

Its closest cousin is Richard Lester’s splintered, cold-shower melodrama “Petulia” (1968). What Lester’s bitter pill was to the hippy-dippy ’60s, Malick’s spiritual balm is to the post-fracture 2010s: Necessary for their time, offering contemplation in an age where we need stimulation, fast, now. Malick’s film believes (either naïvely or bravely) in Romance’s eleventh-hour triumph over an ugly atmosphere of misogyny, drugs, loveless sex, selfishness, snobbery, lack of modern faith and hip nihilism. 129 minutes, with Natalie Portman, Cate Blanchett, Holly Hunter, and (in the best cameo) Patti Smith as a punk Mr. Miyagi of love.

“Frantz” (directed by François Ozon)

François Ozon’s “Frantz”—the cocksure remake of an already great work of art, Ernst Lubitsch’s “Broken Lullaby”—toes the fine line between a poetry of directness and straight-up cliché. Both films are based on the 1931 play by Maurice Rostand called “The Man I Killed.” In the aftermath of World War I, a romance blooms between a writhing, tormented French soldier (Pierre Niney) and the fiancée (Paula Beer) of the German soldier he killed. It was a hit in France; at last year’s Césars (the French Oscars), it tied Paul Verhoeven’s “Elle” for most nominations.

If I agree with the ideals of “Frantz,” I disagree with how it’s executed. Its arty, prestige qualities (“I’m Making an Important Statement about Humanity” and “I’m Improving a Film That Didn’t Go Far Enough”—a deadly partner dance) make it too clean, too hell-bent on an unearned humanism and modernization. Its best shots are inspired by the contemplative paintings of Casper David Friedrich; but these moments whisper “kitsch.” (Watch the scenes of the sailor mulling over his fate in “The Red Turtle” to see Friedrich absorbed — an allusion, not a blatant reference to/copping of CDF’s hard-earned style.) Its chief gimmick is switching colors to match the moods of our heroes: a slick black-and-white in scenes of sorrow, faded colors in scenes of joy and beauty.

But “Frantz” is really quite ambitious, and its patchwork ideas are knockouts. Choice example: the über-patriotic nationalists in a French café singing “La Marseillaise” as Paula Beer and a few other Germans shift nervously in their seats. It’s a great inversion of the famous “Casablanca” scene and its off-putting optimism; it’s even got shades of “Tomorrow Belongs to Me,” the Nazi song from the dark Bob Fosse musical “Cabaret” (1972). Ozon’s adaptation also brings out the queerness of the two soldiers’ relationships. Such tension was there in the gay Rostand’s original play, but were lost in adaptation by the hetero Lubitsch; Ozon—a seminal figure of modern queer cinema—restores them to rich effect. 113 minutes.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.