On Wednesday, two Stanford professors and the founder of Khan Academy discussed educational inequality with President John Hennessy, who moderated the event.

“Combating Inequity in Education” was the latest installment in Stanford’s year-long OpenXChange initiative, which aims to focus campus discussion on national and world issues. The panel brought together Linda Darling-Hammond, the Charles E. Ducommun Professor of Education Emeritus; Sean Reardon, professor of poverty and inequality in education; and Salman Khan, whose online education platform is now used by 37 million students around the world.

In an hour-long conversation that was also live-streamed on the OpenXChange website, Hennessy and the three panelists discussed both the source of educational inequity and also how to address it. The speakers framed the issue as a critical one for many countries around the world, but particularly for the United States.

The problem

Reardon traced persistent inequities in American education to two issues: “unfinished business” with regard to racial inequality and rising socioeconomic inequality.

“Those two forces combine in kids’ lives and in families’ lives to create really segregated communities and segregated schools,” he said.

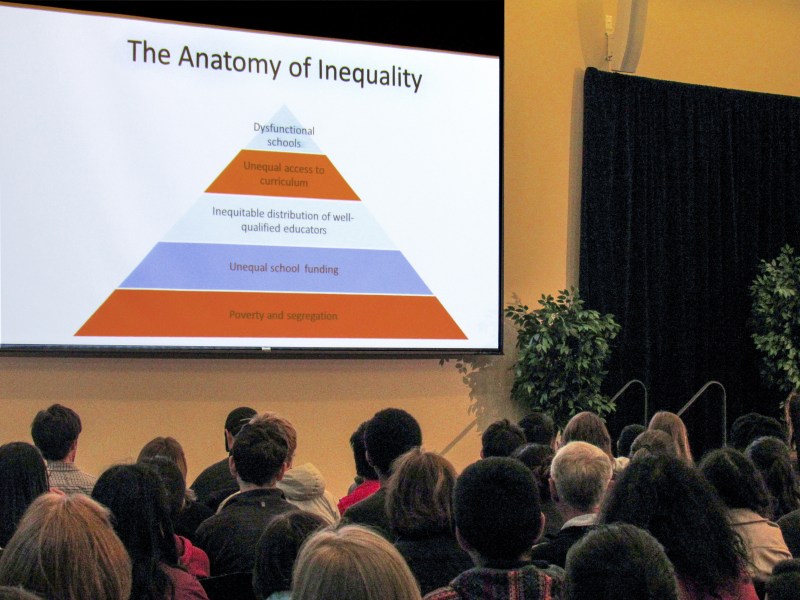

According to Darling-Hammond, de facto segregation of schools feeds a host of related inequities, from unequal school funding to unequal distribution of qualified teachers.

Though Reardon touched on race, socioeconomic disparities dominated the discussion — particularly as Reardon moved on to explain his latest research, to be published Friday. Reardon drew on test score data from every public school district in the United States during the time period from 2009 to 2013 to confirm what many would already suspect: Kids’ academic performances are lower in poorer communities.

Reardon’s research may not be surprising, but his analysis reveals just how striking this correlation is. And it presents a stark picture of just how unequal education is from one area to another: The lowest-performing districts were more than four grade levels behind the highest-performing ones, Reardon found.

However, Reardon took hope in the fact that communities with the same level of poverty can vary significantly in academic success.

“We need to identify those places and think about … the things that make them better places to learn,” he said.

Solutions

While all panelists acknowledged that there is no single silver bullet for inequity, they offered up a number of concrete ways to address the problem. At one point, when Hennessy described educational inequity as a problem that could not be solved “overnight,” Darling-Hammond jumped in to argue that many strategies could yield results in a matter of just a few years.

As an example, she cited Connecticut, which in 1988 addressed a severe shortage of qualified teachers by raising salaries as well as teacher standards. Within three years, the state’s shortage had turned to a surplus, and over the next decade, the state shot to the top of national assessments.

“State policy is what matters in education for the most part,” Darling-Hammond asserted. “States are the agents of change.”

However, she also urged reform beyond the state level.

“We need in this country a policy that most countries have — if you will teach, we will pay for your education,” Darling-Hammond said, to much applause.

Panelists generally agreed on the need to focus more money on low-income schools, where, paradoxically, student populations in the greatest need of resources often get the least funding. Darling-Hammond pointed to research showing that low-income kids had 20 percent higher rates of graduation when 20 percent more money was spent on their K-12 education.

Similarly, all panelists were united on the benefits of preschool, and Hennessy cited statistics that money invested in a child’s preschool is paid for many times over in that child’s future income taxes.

Khan also discussed online education as a tool for increasing equity. He recounted Khan Academy’s origins as one “tiger cousin’s” long-distance attempt to help a family member who was doing poorly in math. After just a few weeks of tutoring, the family member had moved from remedial math into an advanced class.

Thus, Khan believes that online platforms can level the playing field for struggling students who need more targeted help.

“This is the tutor that my family couldn’t afford,” he recalls one Khan Academy user commenting.

Khan also believes that widely accessible online resources can at least partially make up for disparities between schools. For example, a student from a low-income school with few Advanced Placement (AP) offerings can go online to self-study for an AP test.

Although Hennessy mostly left discussion to the panelists, he did offer thoughts on how private universities such as Stanford should help combat inequality, beyond producing research on the subject.

“I do think the private institutions have a responsibility to expand the number of students they have, and not leave that all to the public institutions, which is what we’ve done for a long time,” he said.

For Hennessy, this is more than an abstract idea. In 2014, he told The Washington Post that Stanford planned to slowly increase the size of its undergraduate population. In Stanford Magazine, he mulled adding 100 to 200 students per year.

Audience members talked spiritedly with the panelists during a question-and-answer session. But afterward, some attendees said they were underwhelmed.

“I’ve been in education in California over 25 years, and they’re wonderful speakers,” said one audience member who wished to be identified only as Nancy. “But they say the same old things that I’ve heard over and over again.”

Contact Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.