I like Arizona head coach Rich Rodriguez. I like his defensive coordinator, Jeff Casteel. I think they run a good scheme for the types of athletes that they can recruit. I think that Michigan was wrong to fire Rodriguez for Brady Hoke, I think that Arizona is playing its best football since Dick Tomey was running the show in Tucson and I think that Rodriguez will continue to torment Pac-12 opponents for many years to come.

Also, Stanford beat the daylights out of Arizona last Saturday.

Something remarkable about Stanford’s annihilation of Arizona was that although Stanford overwhelmed Arizona by obliterating them on the line of scrimmage, it used different plays than the ones Stanford is used to. Normally, Stanford’s famous for using the Power play as its base run play – where the offensive line creates a hole off-tackle and the backside guard leads the ball-carrier through the hole – but defenses have been relentlessly crashing that hole for a while now. Against teams that are sound against play-action, it’s harder to punish teams that sell out against Power.

How can Stanford respond when its core play is getting stoned again and again? You can run option plays – the speed option, the read-option with power blocking, et cetera – but even though Kevin Hogan’s legs seem to be back in business, Stanford reasonably doesn’t want to expose him to too many hits. You can try to get the ball to the outside, and Stanford did that a lot, but that seems like a waste of an offensive line against an undersized 3-3-5 defense missing star linebacker Scooby Wright.

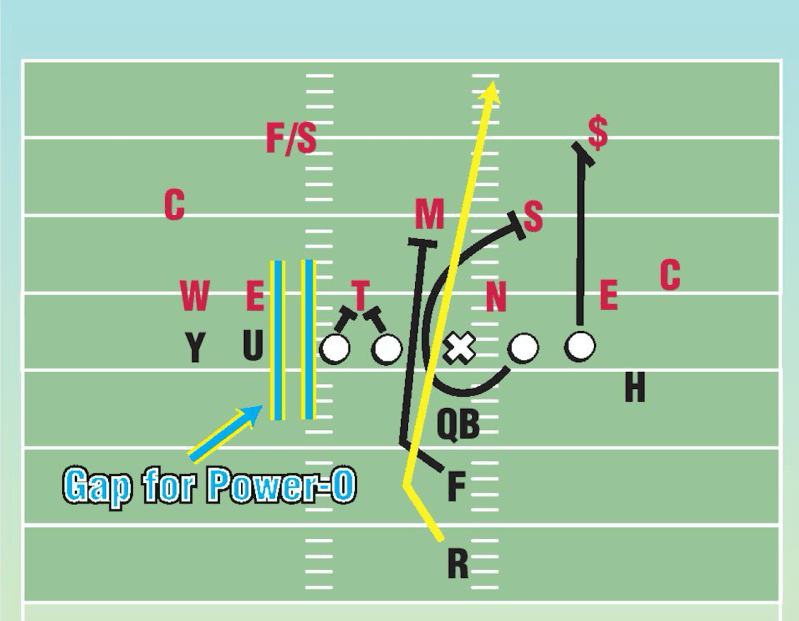

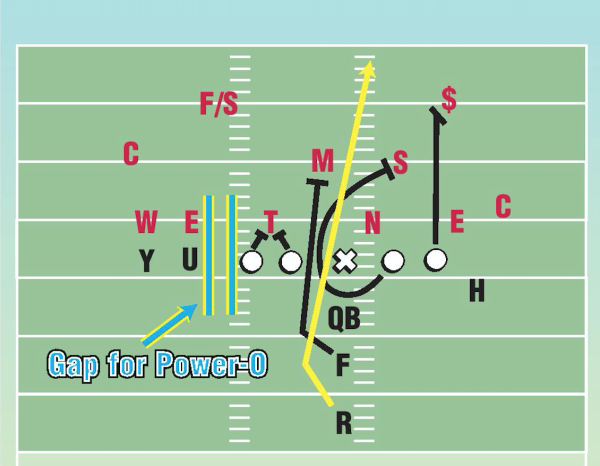

Let’s take a look at a physical downhill running play that, last Saturday, preyed on Arizona’s worst instincts. The Lead O is very similar to Power in a lot of ways: You have a pulling backside guard, you try to move defenders on the line with overwhelming double-teams and you try to create a good hole for the ball-carrier. Instead of Power, however, the play is designed to generate not an off-tackle run, but an off-center run, and the fullback hits the same hole as the pulling guard.

A lot of coaches dislike calling the Lead O because it means that the team is running straight into the teeth of the defense. Ordinarily I would hate it too – against an aggressive defense, two blockers in the hole won’t save your bacon if the defense can read and react properly. You can have a numerical advantage, but if the nose tackle lies down in the middle of the hole, there’s not much a pulling guard can do. In fact, Lead O is often a recipe for a 2-3 yard gain on first down and a mediocre-to-poor success rate on third and short. But if the defense overcommits to Power, the center of the defensive line becomes a weakness, not a strength.

What’s neat about Lead O is that the similarities of this play actually egg on the defense to read it as if it were Power. In the diagram, the defensive end on the left is actually shaded to the inside tight end’s right to make it easy for him to fill the designated gap for Power. The left tackle and guard combine for a double-team, another key component of Power, and the formation includes a fullback, which would normally block the left defensive end on a Power play. Most importantly, the backside guard is pulling – and that’s the action that alerts linebackers to a Power run. The pulling guard is great for play-action; Stanford shows that it’s also great for deception in the run game, too.

Arizona’s 3-3-5 stack defense gives Stanford small holes in the defensive line to begin with (note that the diagram doesn’t show a 3-3-5 stack – it’s based off a diagram from one of David Shaw’s old coaching clinics), and with double-teams Stanford can make these holes bigger. If Arizona’s linebackers bite on the play and think the run is going off tackle instead of up the middle, then Stanford will have two blockers running downhill against linebackers who are headed in the wrong direction. It’s a good play that constrains defenses’ options without sacrificing physicality. If it’s run at the right moment, defensive backs will be forced to tackle, a dicey proposition for many teams. Even if Stanford only gets 5 yards on the play, sustained 5-yard gains will grind any defense to dust. And of course, it helps that Christian McCaffrey can teleport.

Stanford’s countered overaggression with the Lead O before, most notably in the 2013 Rose Bowl against Wisconsin. Even so, you don’t often see the Lead O rip defenses apart like it did against Arizona – but when it does happen, it’s quite a lot of fun.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.