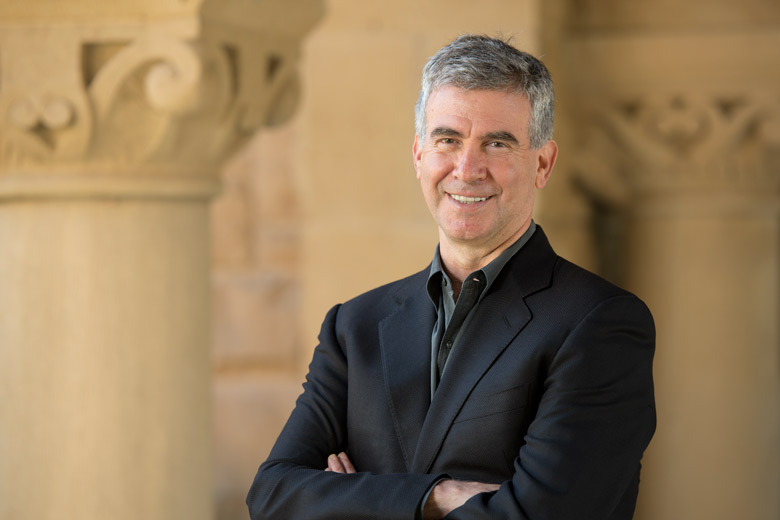

The new dean of the Graduate School of Education (GSE) Daniel Schwartz began his teaching career with an emergency teaching credential, a 1957 grammar book and a class full of kids in south-central Los Angeles.

After graduating from Swarthmore College with a B.A. in philosophy and anthropology in 1979, Schwartz delved deeper into the field of teaching and academia and received an emergency teaching credential, which certifies student teachers to teach in school districts that are experiencing staffing issues. He taught in Los Angeles and Alaska and later received his master’s in computers and education and his Ph.D. in human cognition and learning from Columbia University.

Schwartz has since invested himself in research regarding computers in education, human cognition and education itself. Currently, he is working on a book called “The ABCs of How We Learn: 26 Scientifically Proven Approaches, How They Work and When to Use Them,” in which he explains his research and carves out the curriculum of the courses he teaches.

The Daily sat down with Schwartz to talk about his background in teaching, his journey to Stanford and his goals for the GSE.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What got you started in teaching and education?

Daniel Schwartz (DS): I got my degrees in philosophy with a minor in anthropology when I went to college. When you’re in college, you don’t know what to do. Turns out I could get an emergency credential — so by taking classes in the summer, I ended up teaching in Los Angeles, south-central LA, because they’re having trouble getting teachers. I taught English language arts, and the only textbook available to me was a 1957 grammar book. I had to make a lot of curriculum, and I enjoyed it.

TSD: So you have a master’s in computers and education from Columbia University. How are the two fields related?

DS: [Computers] offer a lot of opportunities. So that was exciting — I could make interesting worlds that kids go through, and [the kids] have enriched, interactive experiences that they just can’t in their daily lives.

TSD: What was your path to the position of Dean of the GSE?

DS: I was asked to interview for this position. I was not sure [about the position]. I have a very successful academic career as it is, and I really enjoy my research. I have a lab of 14 people that I work with very closely, but I was asked to be interviewed, and I really care about education — I care about the school.

The committee, the provost, have a deliberative process where they try to decide does someone fit or not fit, if they’re a good leader. I’m not a part of that [process], so I don’t know how they go about their deliberations. And then I meet with the provost and [President John Hennessy] and have a long interview with each of them. They explain their thinking, and I explain my thinking, and then you get a phone call that says, “Dan, I’m pleased to offer you the job.” And then you go “What? What!”

TSD: As a researcher and professor, what skills do you bring to the position?

DS: I was a professor at Stanford for 14 years. I came here with tenure. So I really know quite a bit about the school, the standards and Stanford. There’s a lot of advantages to [already] being inside [Stanford]. I know a lot of the faculty already; I know their interests; I know some of their concerns. I’m already further ahead in understanding the sort of intellectual energies that are here. I certainly know the students and the kinds of things they like and dislike. I also know a little more about how Stanford works.

TSD: Where do you see yourself taking the GSE as the dean?

DS: I think the GSE has powerhouse faculty and students. So my job as dean is to make the conditions under which they can thrive the best and work together.

TSD: What would those conditions be?

DS: It’s a mistake to come in to a school that is this spectacular with a vision of what they should be doing. They’re the brilliant people — my job is to lead them to establishing a vision that they think is the one that should carry us forward. I certainly have my vision about what I think I would like to have a lot of people working on, but I don’t think I’m dean because my vision of what I think is perfectly right. I’ve become dean to help people: to help them realize their vision that is coherent and consistent and [that] can improve education the most.

One of the things deans can do that faculty can’t is that deans can know what all the different faculty and centers are doing. That gives me advantage because I can see when there are certain places where there can be tremendous energy. But it may be hard for faculty to see that because they don’t know everything. That’s one of the more important roles of being a good leader is knowing what everybody’s doing and trying to figure out places where there can be some great synergies and electricity.

TSD: What do you think needs to happen to improve or maintain the current system of education?

DS: What you need to do is to help these teachers be prepared to continue learning…

It’s tough. It’s an interesting problem. It’s the most valuable thing to provide teacher training so that they continue to grow, thrive. Don’t let them get drawn out. I think our Stanford education teacher program is very good at this. They’re the model for a lot of the country and the world for what are the ways to prepare teachers — to enable them to be really effective. It’s a really good program so as dean, I probably won’t touch them. They’re doing great.

TSD: With all of your new responsibilities, do you plan to continue teaching?

DS: I teach the introductory to teaching statistics course, and I teach the course based on my own theories of learning. It’s a lot of fun and very successful, so I’m going to keep teaching that even though I’m dean. I’ll see how long I can last. It may turn out that it’s a mistake, that I can’t pay enough attention.

[The course] is a good one because statistics is a tough nut, and people are scared of it, and it’s hard to understand. I took all of my theory, [my] teaching expertise, and I tried to see how I can fix this problem, and I think I did it — I don’t want to just stop. I also love it… It’s a good chance to meet students and try to stay important.

Contact Malini Ramaiyer at malu.ramaiyer ‘at’ gmail.com.