In a ramshackle farmhouse doubling as a church, Stanford students and Nicaraguan peasants stood side by side, waiting to receive an unusual communion.

The altar was a beat-up blue table draped in a simple white cloth. The villagers couldn’t afford wine, so the blood of Christ was missing. There was no priest to bless the Eucharist; instead, a woman in jeans and a t-shirt presided over the mass.

A Pope would never have recognized the service as legitimate. But for several of the students in attendance, the homegrown communion ceremony captured the spirit of why they had chosen to spend spring break in Nicaragua.

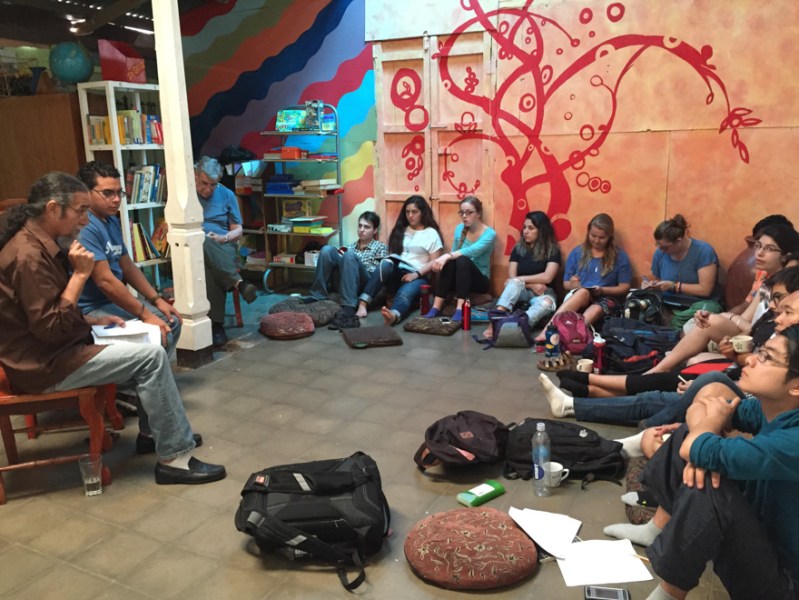

The week-long trip was the culminating adventure of an application-based winter quarter course, Religious Studies 188A: Issues in Liberation. The class centered on liberation theology: the idea that religion naturally leads to active opposition of unjust political and social structures.

On the trip, the class, taught by two Presbyterian ministers and Stanford religious studies professor Thomas Sheehan, saw liberation in action as they met with historians, religious leaders, environmentalists and women’s rights activists fighting to improve the quality of life in Nicaragua.

Students also visited a fair-trade coffee plant, spent time at a center for child victims of sexual abuse, toured churches and museums and stayed a night with Nicaraguan host families.

As they ran through a packed schedule of tours and events, students confronted their own obligations to speak up for the marginalized – potentially by changing an unjust status quo.

“In Nicaragua, a lot of [students] began to say, ‘How do I use my privilege to change the world… to make life better for people who don’t have that privilege?’” said Reverend Abby Mohaupt, a co-teacher of the class. “And I think that’s just been a really stunning question to be asking – such a really humbling and important question.”

According to students, on-the-ground experiences like attending the rural mass in the El Trentino community made the ideas behind the theory of liberation even more real.

“I think it’s only through that deep engagement for a week, where it’s all that you’re thinking about, you actually get a sense of liberation theology…in a way that you can’t get by reading some history,” said Rehan Adamjee ’16.

[justified_image_grid ids=”1098785,1098787,1098788,1098789 ” row_height=250]

Rogue religion

The El Trentino ritual underlined the bottom-up nature of liberation theology – and the related sharp political divide between some Christian communities and church institutions.

In another community the class visited, many in the El Trentino congregation had fought a guerilla war against the Somoza dictatorship, a Nicaraguan political order backed by the Catholic Church. The former fighters considered themselves to be applying Jesus’ message to the struggle against oppression.

“[The community] see[s] their religion and their political issues all wrapped up together,” said Sheehan, who is the head teacher of the class.

Because the liberation theology form of Christianity is based in experience and does not follow an institutionalized dogma, believers consider themselves to be in solidarity with marginalized peoples everywhere – no matter where they fall on the religious spectrum.

The liberation theology movement allies itself with the fight for women’s rights, ecological justice and change in dominant economic and political structures worldwide.

“People thought about religion not in terms of the doctrines or the rituals, they thought about the idea that struggle is spiritual,” Adamjee said. “And that idea is universal.”

For Adamjee, a rejection of the passivity preached by religious leaders who support state power is essential both to his own religious life and to the work he hopes to do with land reform in his home country of Pakistan.

Ramah Awad ’17, a Stanford Out of Occupied Palestine leader, also found that her personal activist struggle on campus connected unexpectedly with her experience in Nicaragua through ubiquitous Nicaraguan displays of support for the Palestinian cause.

“Having spent the last quarter working on these issues…a topic I thought to be completely different turned out to be entirely connected,” Awad said. “People are struggling for similar rights.”

Awad was moved to find support for her own cause in Nicaragua but felt her own contribution couldn’t end there.

“I could continue talking about my experience in Nicaragua, but what am I actually doing to then connect [my own struggles and those of the Nicaraguans]?” Awad said. “Because the trip was so real and raw, I don’t want solidarity to then just be in name or in phrase.”

[justified_image_grid ids=”1098791,1098790,1098792″ row_height=250]

Radical change

The class encouraged skepticism of today’s dominant politics and neoliberal economics and took a hard look at America’s track record of interference in Latin America.

According to Malachi Dray ’18, it’s difficult to find a Nicaraguan who hasn’t lost a loved one at the hands of the Contras, who were U.S.-backed counter-revolutionaries aiming to overthrow the democratically elected socialist government in the 1980s.

“It’s accepted by so many people that our foreign policy [is] doing something beneficial for the world, or that it’s pursuing some conception of freedom or so on, when in reality… it’s important to really closely examine how it’s actively not doing that,” Adamjee said.

Although many students who went to Nicaragua are willing to think critically about the U.S.’s role in foreign affairs, they recognize that there are certain barriers to bringing the trip’s lessons to a larger Stanford audience.

“The thing about a trip like this is that it self-selects for people who already think in a certain way,” Adamjee said. “So for me it’s reinforced certain things, and I’ve become more nuanced in how I think about this stuff, but my core has not fundamentally changed.”

Nonetheless, Adamjee and his fellow 11 students have returned to Stanford with an enhanced sense of the necessity of action.

Sheehan hoped students on the trip would reevaluate the purpose of a Stanford education, searching for the “liberational impulse” in their courses of study.

“What a radical idea, that you would educate yourself to stand on the side of the losers,” he said.

Contact Abigail Schott-Rosenfeld at aschott ‘at’ stanford.edu