In the earlier pages of Samuel Beckett’s novel “Molloy,” the eponymous character muses, “Can it be we are not free?”

Rather than as an interrogation of free will, we may interpret this question literally these days as a question of freedom versus confinement. “Can it be we are not free?” feels like an eloquent rephrasing of the “What do you mean I can’t go outside?” that accompanied the first waves of COVID-19. Now, though we are arguably more accustomed to quarantine, that line, and the rest of “Molloy,” still resonates.

***

“Molloy” is an anti-Odyssey. The first of three novels by Beckett called the Trilogy, it follows two parallel journeys — that of Molloy in search of his mother, and that of a detective named Moran in search of Molloy — in which each journey ultimately ends in the same place it began, the quest unfulfilled.

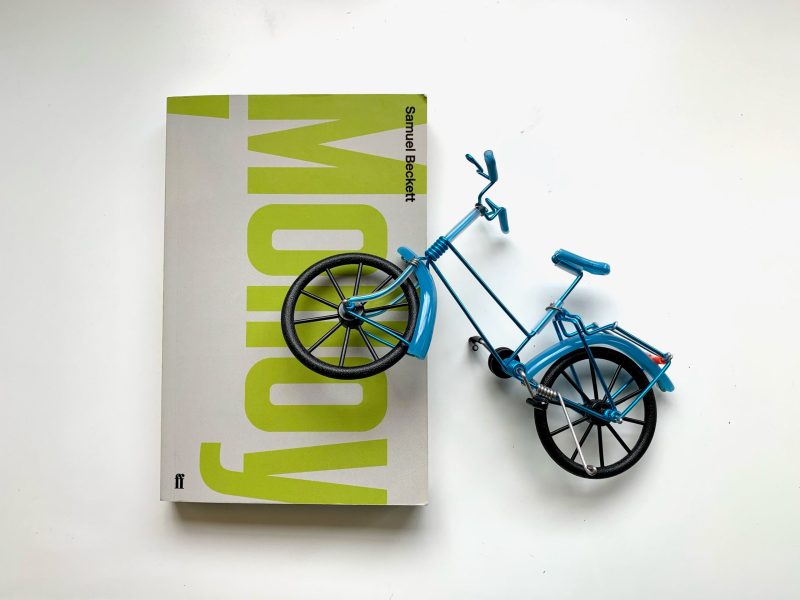

This condition of fixedness dominates the text. Molloy, and eventually Moran as well, is prevented from moving quickly by a leg that no longer bends at the knee. Molloy’s bicycle is old, broken and eventually lost; Moran’s son Jacques runs away from his father and takes their bicycle with him. Many of the most memorable moments of the text (Molloy calculating his average farting rate, Molloy contemplating how to most accurately suck 16 stones contained in four pockets) demonstrate perhaps the most futile and repetitive tasks Beckett could conceive of.

One feels while reading “Molloy” that these characters are so immobile that they even cannot escape the written word itself. With the exception of the first page of the novel, Molloy’s entire narration — just over 90 pages, about half the book — takes place within a single paragraph. He quite literally cannot leave the structure that confines his language, nor can he form his language into the sense-making architecture that paragraphs lend to a text. And as Moran narrates his own journey, one of the symptoms of his devolution into a decrepit, Molloy-like figure is that his paragraphs grow longer.

So, despite their efforts to continue moving forward, these characters can never escape the confines of their unique prisons. Motion is fruitless, meaningless, in the end.

And perhaps that strange world is our world, too. Throughout the pandemic I have often thought of the myth of Sisyphus, symbol of grand futility, sufferer of this daily punishment called sameness. Like the characters of “Molloy,” he is bound to the same path and the same hopeless task for all of eternity. At least with quarantine there is some hope for an end. But still, on days which feel especially pointless, I have found myself circling my bedroom like a shark, maniacally tidying and re-tidying my desk, making and remaking my bed, counting and recounting my collection of pressed pennies, and on and on.

But it seems that neither Molloy nor Moran are bothered by their inaction. While searching for his mother, Molloy accidentally runs over a dog with his bicycle. The dog’s owner, a woman named Lousse, asks him to help her bury the dog in her garden. Afterward, Lousse — like Circe in “The Odyssey,” who uses drugs and spells to turn humans into animals and entrap them on her island, and with whom Odysseus stayed for a year before resuming his journey — drugs Molloy into languidly staying in her home for an entire year. Molloy, however, could care less:

“I accuse her without ill-feeling of having drugged my food and drink with noxious and insipid powders and potions. But even sipid they would have made no difference, I would have swallowed it all down with the same whole-heartedness.”

Moran does not want to escape his confinement either — he actually desires it. As he begins on his journey, Moran bemoans the possibility of never returning home and losing the “absurd comforts” of domestic stability. He takes pleasure in the meandering and repetitive nature of his work, not caring how long it takes to complete it. In this, he notes a solution to the hell of Sisyphus:

“But I do not think that even Sisyphus is required to scratch himself, or to groan, or to rejoice, as the fashion is now, always at the same appointed places. And it may even be they are not too particular about the route he takes provided it gets him to his destination safely and on time. And perhaps he thinks each journey is the first. This would keep hope alive, would it not, hellish hope. Whereas to see yourself doing the same thing endlessly over and over again fills you with satisfaction.”

Contrary to what we may choose, of these two options — the illusion of hope or the knowledge and acceptance of life’s meaninglessness — Moran prefers the latter. As a country we are in love with the idea of hope (just think of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign poster); it’s what keeps us going through difficulty. Every day of the pandemic that goes by, we ask ourselves, “When will it end?” and hope that the answer is soon. But “Molloy” suggests a different answer: “It” will never end. Even when this ends, we will immediately embark on the next equally futile journey, and continue to do so for all of the rest of our lives. Hope prevents us from having to swallow this pill of truth.

Perhaps, then, there is something in the nihilistic resignation of “Molloy” worth considering. If these cycles of meaninglessness are what make up human existence, we may as well linger in the detours when we can — and this pandemic has certainly been a detour, full of the “hellish hope” of a Sisyphus blind to the nature of his condemnation. Let us be a little like Molloy, who, at any point in his journey, “could stay, where he happened to be.”