Despite low completion rates, student isolation and imbalanced demographics, leaders in the field of online learning feel confident that the availability of user data will lead to significant improvements in the future of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

Stanford’s Andreas Paepcke, professor of computer science, works with user-generated data gathered from Stanford’s MOOCs. He has access to all records of student interactions with online courses, down to actions such as pausing videos, submitting homework assignments, posting on forums and more.

By analyzing this data, Paepcke and his team can identify strengths and weaknesses in Stanford MOOC designs. Because of the abundance of available user data which can be used to improve the courses, Paepcke remains highly optimistic about the future of Stanford MOOCs.

“We really haven’t scratched the surface of what could be done,” Paepcke said.

But Paepcke and his team have a long road ahead of them as they work to solve a myriad of problems related to MOOCs.

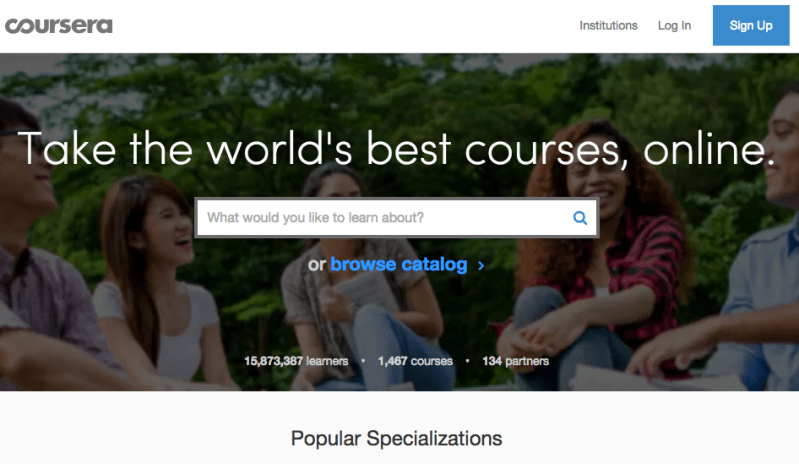

Although initial enrollment rates appeared impressive, the subsequent decline in enrollment numbers as well as course completion rates in MOOC programs such as Coursera — an independent, for-profit platform used by Stanford — proved a disappointment to advocates of the new technology.

Coursera attracted more than 1.7 million students within a year of its founding, according to a 2012 New York Times article. But completion rates continue to remain low, suggesting that MOOCs sometimes fail to teach as effectively as they aspire to.

Udacity, another MOOC platform provider, once saw its completion rate fall to a mere 10 percent, leading cofounder Sebastian Thrun to express his concern in a 2013 interview with Fast Company.

“I was realizing, we don’t educate people as others wished, or as I wished,” said Thrun.

Evidence from a 2014 Social Science Research Network (SSRN) paper by professors at Harvard and MIT also tempered the optimism of MOOCs creators. The paper examined 17 MOOCs from the two schools and found that only five percent of over 800,000 participants ever completed their courses.

Paepcke admitted that online learning currently contains significant flaws, but also provided answers as to why these flaws exist as well as suggestions for improvement.

Paepcke suggested that, because engineers and computer scientists were the first to develop tools for online education, many MOOC templates are designed with engineering and computer science courses in mind.

“We need to try and develop a course that is as far away from engineering as possible, and develop both the technology and pedagogy to teach that online,” Paepcke said.

Additionally, Paepcke believes that user isolation represents one of the biggest problems with MOOCs.

Many Stanford classes have labs or discussion sections with small groups working in a team-based environment. Paepcke suggested that creating a similar group environment via the internet will take plenty of time and effort, but, if achieved, would enrich MOOCs immensely.

Andrew Ng, associate professor of computer science and co-founder of Coursera, shares Paepcke’s optimism. Ng claims that the quality and worldwide impact of Coursera-based MOOCs have consistently increased with the help of data analysis, such as that performed by Paepcke and his group.

Success stories from other universities support Ng’s and Paepcke’s claims that data gathering can help improve course quality. A 2014 report by two professors in Columbia University’s Teacher’s College provided several case studies in which experimentation yielded data to let professors know which techniques worked and which didn’t.

At Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, teachers tried emailing short video clips and small attention-grabbing messages to students, hoping to motivate them to complete their courses, and saw course completion rates rise from 12.5 percent to 19.3 percent.

Between 2012 and 2013, a chemistry professor at MIT asked his on-campus students for feedback on an introductory chemistry course and used the data to re-design the online version of the course with tremendous success; students gaining full credit in the subjects they struggled most in increased from 15 percent to 50 percent.

Although it is easy to gather data from MOOCs, analyzing this data to evaluate effectiveness is a more difficult task.

Schools that are still learning which data is useful to record and which is not sometimes deprive analysts of useful information, according to the Columbia University paper. Additionally, schools often make multiple changes at once when re-designing their MOOCs, making it difficult for analysts to tell which change in particular led to a certain result.

As for worldwide impact, according to the Columbia University paper, Coursera had 22 million enrollees in 190 countries as of January 2014. As stated in the 2014 SSRN paper, just 17 courses from Harvard and MIT garnered over 800,000 registrants.

However, the latter paper noted that the typical enrollee was a “male with a bachelor’s degree who is 26 or older,” demonstrating a lack of diversity in terms of impact.

Though imperfect, evidence shows data may have the power to eventually elevate MOOCs to their full potential. In the meantime, the courses retain their flaws, slowly improving as teachers, analysts and platform providers continue to learn about online learning.

Contact Sean Cummings at seanc3 ‘at’ stanford.edu.