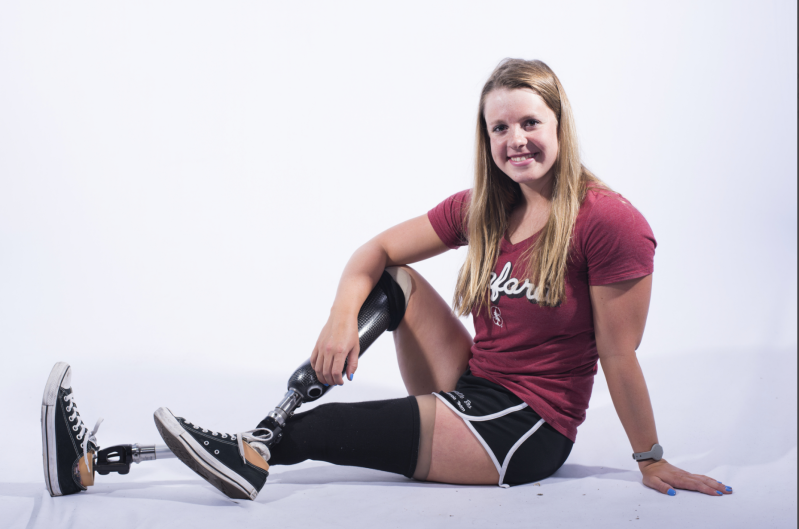

Odds are, Brickelle Bro’s legs are cooler than yours.

“They won’t bite,” Brickelle Bro reassures the children who stare at her.

“They don’t shoot lasers. Wanna touch them?”

Brickelle’s legs are prosthetics – metal poles stuck to skin-colored feet crafted from plastic and carbon fiber. If you accidentally drop them on the floor of the Olympic training center, the rubber feet make them bounce higher than you, according to her teammate Leah Stevens.

Time after time again, those legs wait patiently and without complaint on the Avery Aquatic Center’s pool deck, while the legs of her teammates get ready to enter the pool.

While their rotational mobility might be somewhat limited, their experience in international travel is certainly not: Brickelle’s feet have walked the streets of the Olympic Village in the London 2012 Olympics and will most likely do the same in Rio for the 2016 Olympics this summer.

“But I think the biggest challenge is honestly that people notice first that you’re different, and then define you by that and only expect certain things from you.”

“So I’ve kind of lived my life in a way that’s like, ‘you think I can’t do this? I’m gonna do it. Oh, you think I can’t swim? I’m gonna swim.’”

When Brickelle refers to her disability, she is talking about her legs, which are amputated below the knee due to birth defects. She got her first prosthetics when she was 2 and a 1/2 years old, so it makes sense that she has grown to recognize them as a part of her body.

“I mean, sometimes it’s a little weird when I leave it on the side of the pool deck or when coaches are running it down to the other end of the pool for me because it’s like, that’s a part of me, in somebody else’s arms,” she giggles. She gestures down to her sneakers.

“I mean, that’s my foot.”

While Brickelle has lived her entire life with this disability, she has never let it limit her.

“I have a disability, but I’m not disabled,” she points out. “It’s not who I am and I’m not limited by anything.”

She is dynamic and eloquent, humble and powerful – both inside and outside the water. Her parents have played a big part in defining her relationship with her disability.

In accordance with preschool social norms in Castle Rock, Colorado, she got into sports early, starting with the classic gateway drugs of soccer (“but I don’t like running at all”) and ballet (“which I loved, until I could no longer point my toes”).

She says she finally got into swimming as a result of her mom’s encouragement.

In the Bro family, there are two things you must know: how to play the piano and how to swim.

Brickelle recounts her first swimming lessons with her brother, and how she loved swimming almost as much as her brother hated it.

There’s a reason paralympians call water “the great equalizer.”

“While I can’t walk on land, I can do this in the water and no one can even tell that I’m different,” she says. Swimming was different for her from other sports because Brickelle didn’t feel like she was immediately disadvantaged due to her inability to run.

She first joined a summer swim team and eventually began swimming on a year-round club team. By the time she got to high school and began swimming with the Rock Canyon Swim Team, Brickelle had found a second home in the pool.

While she swam against able-bodied classmates on both her swim teams, it was the Paralympic meets that really meant everything to her, though she only competed once or twice a year. Her talent and drive within that field put the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic games on her radar even before she was 15 years old.

It was natural, then, that Brickelle’s coaches would want bring her to the 2012 London Olympic Trials, to, you know, test the waters.

She would get a taste of what Olympic-level competition meant and be back in four years to try again. Her coach prepped her for what he thought was coming – a “don’t get your hopes up, this is just a fun meet” speech, according to Brickelle.

“My coach was like, ‘there’s no way you’re going to make it,’” she says.

She made it, of course.

“My parents didn’t even have a hotel room for that night because we were just going to go to the meeting, see who made the team and then leave. But I made the team, and then we had to stay for a bunch of meetings, so that was a surprise.”

So, in 2012, high school freshman Brickelle took a plane to London for her first Olympics.

“There are not even words,” Brickelle says when I ask her about the Olympics. “It’s … I mean … give me a second. Because it’s … ”

She trails off again.

“There’s just not words.”

She’s smiling at something — a memory that jumps to mind.

“My favorite story was when I was walking to the dining hall, and a guy from Italy fell off the curb in his wheelchair and fell over and was, like, on the ground sideways. A coach from Russia and a coach from Spain rushed over to help him up,” she says.

“We [the Paralympic athletes] don’t even speak the same language, but you feel like a family because you’ve gone through so many of the same things, even though they weren’t together.”

Brickelle ended up placing fifth in the 2012 Paralympic Games in the 400 freestyle. By the end of her high school career, she had set the S8 Paralympic American records in the 1,000-yard free and the 1,650 free. She gets stronger and faster with each day of training; just this year, she broke the S8 Paralympic 1,650 free record for a second time.

London was definitely a surprise.

Rio, on the other hand, is a different story.

Brickelle’s eyes were fixated on Rio before the London Olympics had even happened, and they’ve been deadlocked on Rio ever since. She’s got five Mondays until Olympic trials, and she’s looking for a medal.

Knowing that she was going to be training for Rio for freshman year, it was important to Brickelle to go to a college that allowed her to practice with their swim team. Because Brickelle wasn’t recruited like most swimmers, she has had to fight for the resources to succeed.

The second after sending in her Common App, Brickelle emailed Stanford head women’s swimming coach Greg Meehan – a polite letter saying, “hey, I just applied to your school, and I really want to talk to you about training with your team.”

Brickelle applied to seven schools and got into six, but Stanford was the only school that would gave Brickelle an audience for a trial.

When she got her acceptance letter, Meehan emailed her about joining the team before she even got the chance to tell her grandma the news. Brickelle’s spot as a Cardinal swimmer was solidified when she met Meehan and the team over Admit Weekend and charmed them into what Meehan describes as an “pretty easy decision.”

While he admits he was reluctant to commit to Brickelle over electronic communication, Brickelle’s competitive drive and thoughtful nature swayed him when they met in person.

Yet, as Brickelle would soon realize, walking onto a team at Stanford is not easy, especially a team as competitive (and arguably cultish) as the Stanford swim team. The girls eat, sleep, breathe, stretch, cry and win together – forming a rare bond that is difficult to share in as an outsider.

“I was terrified about fitting in,” Brickelle says. “Everyone knew each other. I was afraid, because it felt like I had to beg to get onto the team and I was worried that people would be like, ‘oh, she’s not fast enough, blah, blah, blah,’ because that was the kind of response I’d gotten from other people in other colleges.

“But getting here, no one has ever treated me like that, and it’s a blessing.”

Actually, it turns out that Brickelle’s teammates were just as scared of her as she was of them.

I ask freshmen Leah Stevens and Kim Williams, two of Brickelle’s best friends on the team, what it was like to meet Brickelle for the first time.

“I was a little nervous,” Kim admits.

“Yeah, she seemed like a badass. Like, she sounded so cool,” Leah said.

“Our coach had sent us a SwimSwam article, which is like a swimming blog, about her, saying ‘this is your new teammate, read about her – ’” Kim begins.

“What? I didn’t know that.” Brickelle interjects, looking dumbfounded while sandwiched between her two friends on the couch.

“So we actually emailed her before we met her,” Kim continues, turning back to me, “because she was going to the Paralympic World Championships in Scotland or something, so we emailed her good luck.”

“But yeah, we were a little intimidated. I remember we met at the Marriott across from Stanford, and we still hadn’t decided how to pronounce her name either, so that was an immediate stressor for us,” Kim said with a laugh.

Before school each year, Stanford women’s swimming takes a pre-season trip to Maui. This trip is part of the secret to the close-knit nature of the swim team. It was also when Brickelle’s teammates really got to know who they were dealing with for the first time.

“One thing about Brickelle is that you forget there’s anything different about her,” Kim says. “You don’t know she’s disabled, like she doesn’t act like that at all.

“The moment I realized that, we were in Maui, going into the ocean. She took off her prosthetic legs to get into the ocean and I was like trying to help, like, ‘oh, do you want me to carry you in?’ I think I was trying to hold her hand.

“And she said, “no, you can get away from me, I got it.’

“I was like, ‘woah, okay,’” Kim says.

“Oh, was I that mean?” Brickelle’s brown eyes widen, and so do mine. I literally can’t picture her saying anything mean, ever.

“No, it was just sassy, like ‘that’s the way it’s going to be, and that’s the way it’s going to be for the next four years.’”

“It’s awesome how strong and independent she is. She’s like, ‘nope, I’m good, I don’t need you. Maybe as a friend, but I don’t need your help with anything.’ And we’re good with that.”

Seriously – mention Brickelle’s name to anyone who knows her, and they will start raving.

Her teammates paint a word picture of Brickelle doing pull-ups with a huge weighted plate, and her coach mentions that she thanks him every time she gets out of the pool at practice.

Kim, who’s proud to say that her locker is right next to Brickelle’s, says that she can’t imagine doing as much free stroke as Brickelle does.

Leah, a fellow distance swimmer, even gets a little emotional telling Brickelle how much her extra “let’s go, you got this” means to her during those hard sets, when it’s just the two of them doing a workout together.

But even with her distinguished international record, ask Brickelle what she’s most proud of in her life and you’ll get an answer you might not expect.

It’s not London. It’s not her All-American records. It has nothing to do with the way she absolutely crushes life despite the fact that she was born without real legs.

It was getting into Stanford.

“I think it was hard for her at first,” Meehan says. “I think any student that comes to Stanford is immediately … overwhelmed by how many smart and successful people are walking around campus on a daily basis.

“That’s hard for everybody … I think for her, it’s even more so, because she’s part of this Division I program, knowing that there are not many Paralympic athletes doing what she’s doing.”

But it’s clear now that that Brickelle has found her niche at Stanford.

If her record-breaking swims, inseparable friendships and infectious laugh weren’t telling enough, one needs look no further than the Pac-12 Championships, where Brickelle completed the 200 freestyle and the 500 freestyle alongside the most talented, able-bodied Division I swimmers in the country.

Outside of swimming, Brickelle assures me that she is “a normal person – sometimes.”

“I eat a lot, and I like to watch movies and read books. I really, really enjoy filming and editing videos.”

But at the end of the day, Brickelle is one of those genuine human beings who does what she does because she loves it.

It’s clear, now more than ever, that Brickelle has found an identity in swimming – her passion for it defines her far more than her disability ever has.

“For me also the pool has always been … ” she lets off.

“I don’t know … home?” she says.

“No matter where you are, the black line always looks the same at the bottom of the pool, the water always feels the same, and it’s how I relieve stress a lot of the time.

“It’s always been a part of my day, and it’s where my team is and where I know what I’m doing. The disability never comes into play.”

Contact Kit Rampgopal at [email protected].