Montage is at the heart of three compelling exhibitions at the de Young Museum. In Danny Lyon’s photo gallery “Message to the Future” (closing this Sunday, April 30), the source of the pathos is the splicing together-act itself – snapshots of humans culled from disparate corners of the world (Civil Rights activists, undocumented workers, Colombian street kids, prisoners, drifters like Faye Dunaway in “Bonnie and Clyde”), the eyes all meeting at the center of a deeply sympathetic camera lens. Downstairs, “The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion & Rock ’n’ Roll” (up until August 20) offers a local look into a crucial part of American history, when San Fran was the center of pop culture and the smell of revolution was pungent. The buzz and life of these two exhibitions drifts slightly upstairs to “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing” (up until August 6), where a destructive interference effect (endless modernist collages canceling each other out) ensures that most of Davis’ sweet-jazz canvases blur in the recalling mind. (I’ll talk about the Davis exhibition in tomorrow’s paper.)

Danny Lyon’s “Message to the Future,” celebrating fifty-plus years of the illustrious photographer’s career, is too hard to leave. One of the 20th century’s most powerful photographers, this rightful heir to Robert Frank’s “The Americans” snaps shots with a confidence that hits your spirit in gentle waves. As the official photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lyon captured lunch counter sit-ins, the March on Washington, police brutally beating nonviolent activists. For five years (1962-67), he joined an outlaw motorcycle gang, capturing the casualness of societal outsiders with interviews and arresting portraits. For 14 months in the early 1970s, he took pictures of Texas prisoners, going far beyond the social importance of such work into a rarely attempted terror. His prolific filmmaking oeuvre (which I have to start immediately) covers a range that’s just as wide: homeless Colombian kids (“Los Niños Abandonados,” 1975), tattoo artists (“Soc. Sci. 127,” 1969) and his own father and son (“Two Fathers,” 1982).

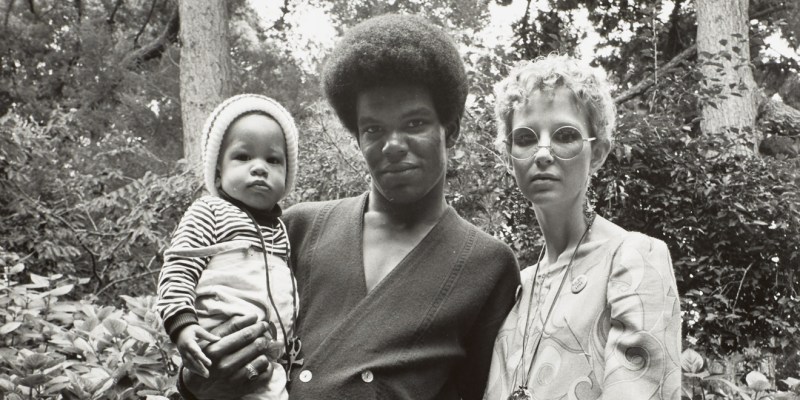

It is Lyon’s willingness to stay close to his subjects (encouraging them to look straight into the camera, skirting to the edge of private danger zones in frighteningly cinematic close-ups) that gives these pictures their social and artistic power. Like Frank, he understands America because he is unafraid of intimacy. But unlike Frank, he shows Apollonian calm and reservation. He eschews the frantic Frank need to capture the ephemeral present, here, now! Instead, time and experience are allowed to pool into untouched, never busy, still lives. The relaxed, unreadable look of Kathy (one of Lyon’s subjects, with whom he fell in love) hints at so much rich backstory; she is like that supporting character in a film you want to follow, but never will. They are the more interesting people anyway. The world belongs to them. Time and again, Lyon’s photography understands this principle: (1) The boy with a tucked, button-down shirt in “Uptown, Chicago 1965” is uncertain and unbearably proper, in a world far away from his three snarky, tough-looking friends, (2) the hazy men shooting lonely pool like a scene straight out of Ken McKenzie’s 1961 docudrama on Native Americans, “The Exiles,” the unexcitable city hangs just centimeters away from sight and (3) the hauntingly foreshortened hobnail boots of two undocumented workers near the Mexican border – seen only for what they do (work), not who they are (face).

“The Summer of Love” presents a different view of city life – less beautifully fragmented, more specific and kooky, but with a still notable diversity. The exhibit marks the 50th anniversary of the legendary Summer of Love in San Francisco, when more than 100,000 young people came in droves to the neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury in 1967 to kickstart a revolution. History has tended to relish the failure of the so-called hippie movement, as the 1970s hangover of Law-and-Order Nixon, Watergate, oil crises, and deep American cynicism kicked in. But “The Summer of Love” isn’t meant to be either a come-on or a come-down; it’s somewhere in between, with a timeliness that invites a look-back into history to see what the hippies got right.

It’s pretty shocking to see the scale of the experiment. In Jim Marshall’s 1968 photo of a Grateful Dead concert on Haight Street, you can’t even see the sidewalk, it’s so teeming with hairy bodies. In a poster advertising three free classes of “survival school,” or “how to stay alive on Haight Street,” the roster of activities is telling: Monday nights at 8 p.m., you learned about drug lore (“how to keep from getting killed for kicks”); Tuesday nights, same time, there was sex education (“how to avoid gangbangs, rape, VD & pregnancy”) and a lesson on Street Wisdom (“how to avoid beatings & starvation, how to survive without money”); Wednesday nights, experienced hippies taught the babyish newcomers the way to live. Buttons with witty truisms announced who you were to the world, and where you stood: “I am a beautiful people” – “I’m manic depressive, be warned” – “If you are not part of the solution, you are part of the problem, [Black Panther Eldridge] Cleaver” – “I’m a member of the L.S.D. for lunch bunch” – “Would Christ carry a draft card?” – “Mary Poppins is a junkie” – “I’m from Berkeley, but I’m not revolting!” – “You’re sitting on my hair.” In a letter typical of the times’ fervor, a 12-year-old girl asks to be part of the hippie movement: “My sister dose (sic) not like Hippies and will not let me come into her room. My mother under stands me and Hippies. I took some clay and made a hippie love Peace sing (sic) and where (sic) it around my neck as a necklace. I understand Hippies.”

The “poster shop” – psychedelic designs announcing the next performers at Bill Graham’s famous Fillmore Auditorium – is a real treat. Only in 1960s SF could you have a double bill with swamp-rocker Leon Russell and Miles Davis, or comedian Lenny Bruce and art-rock Mother of Invention Frank Zappa. The Fillmore posters want to look cool while flirting with complete unreadability. Most pass the first test.

They talk about “living history,” but when it’s something as massive and popular as the Summer of Love movement in San Francisco, you really feel it. As I was looking at copies of the San Francisco Oracle (the hippies’ short-run yet wildly popular magazine), I couldn’t help noticing an old man with a snazzy silver vest and smart spats. He didn’t have the smell of hippiedom on him; but the subtle smile and bashful look on his face betrayed the disguise. Two teen boys (maybe relatives or sons?) were letting him reminisce. “After a while,” he explains to the young’uns, “most people ended up selling all the copies of the ‘Oracle’ they had. But I never did. I still keep all of these” – he points to three covers – “and, of course, the Monterey Pop edition.”

Suddenly, the room came alive. Yes, tons of other people were there who certainly lived through the Summer of Love. Yes, the aging, brown Monterey magazine, fixed behind protective glass, gave me a glimpse into that particular event. And yes, the label on the wall explains how Bay Area newspapers would give 10 copies of the “Oracle” to any young person who wanted to sell them as a means of financial support. Yes – the history is there and on the museum wall. But what makes the exhibition real was someone delving deep into their memory, beaming with pride at having lived through it. A buzzing part of history in San Francisco surged through the room – and it’s damn exciting to be next to it, however secondhand. What the hippies harnessed that hot ’67 minute was a mind-boggling synchronicity of goals — something we probably won’t see in America anytime soon.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.