Stanford is well known for being a physical running team, but despite a brutal downpour that would cause most teams to favor a running attack, No. 5 Stanford bucked the trend and threw the ball all over the field last Saturday. Junior quarterback Kevin Hogan was positively surgical in his precision as the Cardinal demolished the Washington State Cougars 55-17. Curiously tied at 3-3 late in the first quarter against one of the worst teams in last year’s Pac-12, Stanford broke the game open with a deep strike to receiver Devon Cajuste, and it was all Cardinal from there.

Washington State’s aggressive defense had shut Stanford down on the previous two plays, and Stanford was facing third-and-9 at its own 43-yard line. Seeing a chance to burn the Cougars for their aggressiveness, Stanford sought refuge in audacity and attacked downfield.

In recent years, with the growing popularity of spread offenses reliant on speed, pundits across the country have lauded Stanford for its old-school power running system. But contrary to popular belief, David Shaw prides himself on his multiple-formation offense, and needing a big gain, the Cardinal brought in a standard spread set with four wide receivers — hardly old-school. Having spread players across the field, Stanford called one of the archetypal spread offense plays: three verticals.

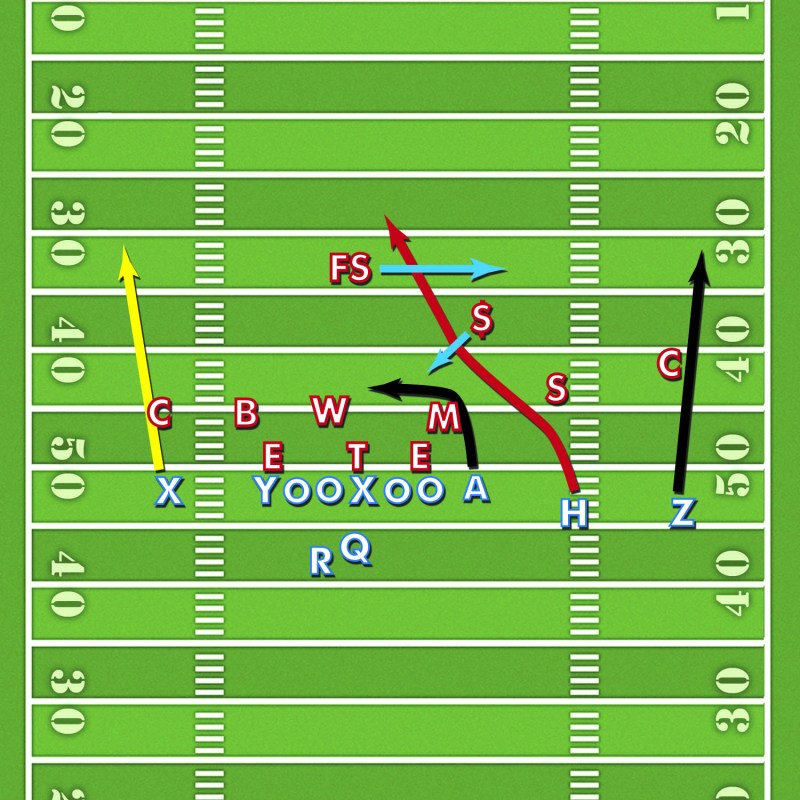

Anticipating a pass play, Washington State showed a conservative two-safety look. Even after the Cougars blitzed five players, they still had six defenders remaining to deal with Stanford’s four deep threats — a numbers disadvantage that is the cornerstone of most criticisms of the spread offense. Washington State looked to have the best of both worlds — a solid two-safety coverage and the ability to play an aggressive man-to-man coverage underneath.

But Stanford had a key advantage: the positional mismatches caused by its two extra wide receivers. Specifically, Washington State was forced to line up slower linebackers (S and M) against speedy receivers Michael Rector (A) and Devon Cajuste (H). Against Rector, the Cougars compensated by adding safety help ($), but Cajuste was now one-on-one against a slower player.

Here the spread helped pave the way to victory: By spreading the receivers and stretching the field, Stanford opened up space to run. Stanford’s three deep vertical routes pinned Washington State’s cornerbacks to the sidelines, clearing out the middle of the field to let Cajuste find the open space. With three receivers to the right of the quarterback, Washington State’s remaining safety (F/S) overcommitted to the right. Cajuste easily outpaced his man, drifted left and found daylight in the middle of the field, and his 57-yard touchdown catch gave Stanford a lead it would hold for the rest of the game.

Stanford repeatedly burned Washington State on vertical routes on Saturday, not just with Cajuste but Michael Rector as well. By forcing one-on-ones, Stanford’s spread minimized Washington State’s margin for error, and with positional advantages in hand, the Cardinal made Cougar errors almost unavoidable. That’s not to say that the spread is the perfect offense, but it has its uses, and when your score is that lopsided, you did something right.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94‘at’stanford.edu.